Austrian Economics

The Perspectives of Pluralist Economics

Explore Perspectives Compare Perspectives

This text presents a perspective of Pluralist Economics. In the orientation section you can learn about and compare ten different perspectives of Pluralist Economics.

Authors: of the exploring economics team | 18th of December 2016

Patron and academic review: Prof. Dr. Friedrun Quaas

1. Core elements

The inception of the Austrian School can be traced back to the work of Carl Menger, himself an Austrian economist. Representatives of this particular economic perspective are therefore often referred to as ‘Austrians’ even though they have no geographical attachment to the country. Menger’s economic analyses emphasized subjectivism, utility and marginalism (Quaas und Quaas 2013, 34). Subsequent scholars working in the tradition of the Austrian school have expanded the canon by adding several core concepts. Authors – both those who self-identify as ‘Austrian’ and others who do not – have stressed the following as being distinctive properties of the perspective (see e.g. Holcombe 2014,107ff; Radzicki 2013, 145; Milonakis and Fine 2009, 254–25; Blumenthal 2007, 34–35; Hagemann 2010, 188):

● methodological individualism;

● opportunity costs;

● subjectivism;

● laissez-faire policy (recommendation);

● emphasis on dynamics and time in economic processes;

● fundamental uncertainty;

● relevance of prices and free competition;

● a monetary theory of crises;

● a focus on the entrepreneur;

● apriorism and strong deductivism; and

● aversion and mistrust against the use of mathematical and statistical methods in economics.

In the remainder of the text these core concepts will be explained in more detail.

Considerable time has elapsed between the publication of Carl Menger’s Grundsätze in 1871 and the publication of the writings of contemporary Austrian scholars (the so-called New Austrians), within which there has been lots of activity. Menger, who can be considered the founder of the perspective, was a central figure in the marginalist revolution in economics and made a huge contribution to the development of the theory of subjective value and to the theory of diminishing marginal returns. In the course of the 20th century, the Austrian school, however, had to deal with historical breaks, which have to do with the forced emigration of its members from Europe to the US during the Second World War as well as with the marginalization of its representatives in academia by the mid-century. This ‘turbulent history’ makes it difficult to draw a consistent and uniform picture of the Austrian school that could be considered a linear and coherent development, starting with Menger and leading to contemporary scholars. Therefore, treatments in the history of economic thought have divided the Austrian school into four – or five if one was to count current Austrians – generations or stages (Quaas und Quaas 2013; Blumenthal 2007).

The historical and analytical differences between these different generations will be discussed more extensively in section 8. However, the remainder of the text develops an ideal type description, which stresses the commonalities in Austrian thought rather than the differences.

In doing so, the self-descriptions of New Austrians will serve as one source among the many. In this context it is necessary to note that marginalized perspectives in economic thinking have consciously tried to describe themselves as a coherent paradigm. This forms part of a political strategy, since they then can present themselves as well-developed alternatives to the mainstream (Backhouse 2004, 268). As a consequence, the self-description of the New Austrians will be assessed in a critical manner and supplemented where necessary in the following text. By doing so, the intention is to prevent the reproduction of a ‘Bastard Austrianism’ (Quaas und Quaas 2013, 33), which consciously or unconsciously mis- and re-interprets the thinking of the original Austrian school.

2. Terminology, analysis, and conception of the economy

The focus of research that is carried out in the tradition of the Austrian schools lies in the investigation of economic coordination among individuals. This theme is to a certain extent already visible in the work of Menger (Blumenthal 2007, 36). Yet, Menger’s main concern was the tension between human needs and scarce goods, which are exogenously given. This puts his analysis of the central economic problem closer to the neoclassical school, which also stresses efficient allocation of resources (Yagi 2010, 32–33). However, the Austrians, who refer to the work of Friedrich A. von Hayek, are less concerned with investigating market equilibria or the efficiency of markets (cf. Holcombe 2014, 51). Instead, the market economy is conceived as a coordination mechanism that enables individuals to make use of information in order to plan their economic activity in such a way that ultimately will be consistent with the plans of all other economic actors. This proposition of the Austrians leads them to a positive assessment of markets. Still, it is acknowledged that this coordination mechanism does not always work perfectly. Hence, for the Austrians, one of the most important goals of economic analysis is to find out why the coordination might break down from time to time (Holcombe 2014, 2). Generally, the research of the Austrian school is concerned with understanding the processes related to the allocation of resources, and the coordination of plans for demand and supply (Holcombe 2014, 5).

Austrian economists conceive of the market as a market process. A central assumption is that coordination of individual plans for supply and demand never works perfectly because plans concern the future and are hence subject to fundamental uncertainty (Holcombe 2014, 1).As a consequence, an equilibrium of prices and quantities of goods and services can never be reached. So while there are tendencies that pull markets towards an equilibrium state, Austrians argue that the market environment is subject to continuous changes in preferences, technology and knowledge. Furthermore, the information that is necessary in order to arrive at an equilibrium is considered to be dispersed throughout all the participants in the market, which makes an aggregation that will result in an equilibrium state impossible. Thus, for the Austrians, the market equilibrium is only a hypothetical concept, which has nevertheless been used by some of their representatives for analytical purposes (e.g. Hayek 1976, in Quaas und Quaas 2013, 142). Still, they argue that it cannot be considered to be an adequate description of reality. Instead, market equilibrium is conceptualized as a continually moving target. Markets tend to clear, but once the existing configurations of prices and quantities are disrupted, these disruptions lead to a wholesale change in economic circumstances, which impedes the economy from returning to the state it found itself in prior to the disruption (Holcombe, 2014, 11).[i]

Another analytical element of the Austrian school is the concept of spontaneous order, which denotes the orderly state that arises from the decentralized plans of individuals and was coined by Hayek (1960, 38). The results of the market process are accordingly interpreted as the ‘results of human action, but not of human design’ (Hayek 1969, 97–107). This assessment illustrates that, in the eyes of Austrians, central planning or designs and predictions that are carried out by governments are considered to deliver no or very limited economic performance. Instead, the Austrian perspective concludes that central authorities can neither predict nor control the behaviour of individuals (Holcombe 2014, 4).

For this decentralized and individual economic coordination of plans via the market to function, according to Randall Holcombe, it is decisive that new information emerges through the market process (Holcombe 2014, 10). This function of the market is illustrated by the conception of the market as a discovery procedure. Accordingly, the market generates information about the continually changing relations of scarcity, which in turn, enables individuals to adjust their future plans to the changing conditions and deal with contingencies (Holcombe 2014, 10). Referring to the work of Hayek, it is important to note that in this context, markets are understood as competitive markets, since said information can only be generated in a situation of competition. In order to illustrate the discovery function of the market, Holcombe uses Leonard Read’s example of the production of a pencil. The production of the pencil requires a complex coordination of activities that are carried out by different people in accordance with the division of labour. Only by means of the process of market exchange is it possible to discover the necessary information about the prices of the factors of production (e.g. graphite); as a result, the producers are then enabled to decide which combination of materials they will use in the production process. The market, thus, discovers the value of the factors of productions as well as the value of the subsequently produced goods and services. Meanwhile, the market prices aggregate the information from different market participants. As a consequence, the pencil producer does not have to know how to mine graphite in order to be able to use the knowledge of those who do know about the mining process. The knowledge stays decentralized and yet the activities of the economic actors are coordinated in such a way that in the end a fully functional pencil is brought into existence. Representatives of the Austrian school contend that in the absence of market prices, economic actors would only have a very limited capacity to coordinate their economic activities, because knowledge is characterized by its decentralized and tacit character (Holcombe 2014, 14).

Regarding the production sphere, members of the Austrian school distinguish between management and entrepreneurship. Finding the optimal combination of inputs, and their optimal quantity, in order to arrive at the most efficient way of producing via a given production function is labelled the management function of a business. In this case, the parameters of the production function are taken as predetermined. Entrepreneurship, by contrast, denotes the discovery of so far unexplored opportunities for profit. This is achieved by developing new ways of combining factors of production, as well as by adding new factors of production and by (qualitatively) altering the output of the production process. Entrepreneurship, thus changes the production function itself (Holcombe, 2014: 24).

The concept of entrepreneurship is a central element of the Austrian school, because the welfare-increasing effects of the market process depend on it. Neoclassical economics develops the concept of a Pareto-efficient equilibrium, denoting a state in which nobody can increase welfare by additional transactions without making others worse off. For the Austrians, however, such a state can never be achieved. Instead, they hold that welfare is continually increased through entrepreneurial activity and innovation.[ii]

Yet another important aspect that features prominently in the analyses of the Austrians is the focus on the monetary economy and the dynamics associated with it (Hagemann 2010, 183). Carl Menger started this tradition of enquiries by developing a theory of (commodity) money, which takes an evolutionary perspective on the development of money, stating that the emergence of money can be explained in terms of a spontaneous order of individual action and not in terms of deliberate government intervention (Menger 1892, Holcombe 2014, 3–4).

In his theory of capital and interest (the so-called Agio theory), Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk elaborated the thesis that goods in the present are considered to be more valuable by individuals than future goods. This reasoning is often used in contemporary economics and offers a justification for the existence of interest. Böhm-Bawerk further explains the process of value creation, i.e. the capacity of the producer to generate revenue that exceeds the interest. He argues that this can be explained by the fact that the producer will employ the borrowed money to acquire capital goods, which in turn, can be utilized to expand the production process adding further stages. These additional stages, which increase the time frame as well as the technological sophistication of the production process are more successful, because by introducing intermediary steps into the production process, output is increased both in terms of quality and quantity (Quaas und Quaas 2013, 69–72).[iii]

The process-oriented understanding of the economy has also inspired another field of research that is of special interest to the Austrian school. Members of the school have made several attempts to grapple with the problem of business cycles. Joseph Schumpeter (1911), Friedrich von Hayek (1931), Gottfried Haberler (1937) and Ludwig von Mises (1949) amongst others, have developed theories of business cycles and economic crises. Whereas Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction emphasizes the creative destruction of established economic sectors by entrepreneurs and deals a lot with innovation processes, the other explanations put (endogenous) monetary dynamics at the centre of their analysis. The theories regarding monetary dynamics and financial crises have experienced renewed interest and controversial discussions in the course of the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. Therefore, in Section 7, the Austrian Business Cycle theory as developed by Mises and Hayek is elaborated and scrutinized.

There is still so much to discover!

In the Discover section we have collected hundreds of videos, texts and podcasts on economic topics. You can also suggest material yourself!

Discover material Suggest material

3. Ontology

The Austrian school subscribes to a strong subjectivism as well as to a methodological and maybe even ontological individualism (Blumenthal 2007, 35). Subjectivism means that the only existent world is the one that is perceived by individuals. Even though this at first appears to be an epistemological statement it nonetheless has ontological implications, since it stipulates that the social facts – like prices and costs – exist only inside the individual (Hall and Martin 2011). As a consequence, even though aggregates or institutions might be discussed, they can always be reduced to individuals, since they and their actions form the starting point of such entities (Hall and Martin 2011, 4).

The economic problems of these individual actors are the coordination of plans and the aggregation of knowledge. Individuals in the economic context can either act as consumers or as entrepreneurs. Consumers articulate their demands, which determines the shape of the market, whereas entrepreneurs are capable of detecting yet unexplored demand (Holcombe 2014, 21, 24). This focus has strong associations with uncertainty, the dispersion of knowledge and information and the change of environmental conditions in historical time. Older representatives of the school, however, prioritize the problem of the allocation of scarce resources (cf. Yagi 2010, 27).

The way in which Austrians conceive human nature is to a certain extent similar to the view of neoclassical economists. Still, some Austrians have developed a more elaborated image of human nature. Whereas Menger defended the rather simplistic understanding of the analytical construct of the homo economicus with instrumental rationalism, utility maximization, and perfect information (Quaas und Quaas 2013, 38), other Austrians have incorporated social components such as institutions, power and the social environment into their view on human nature (e.g. Wieser, cf. Arena 2010, 112–113). This acknowledgement of contextual factors does however not mean that the focus on the individual alone as the acting subject is dropped. Instead, it only means that the actions of the individual will change insofar as it receives varying input depending upon the historical context.

Another way in which at least the newer generations of Austrians differ from neoclassical economists is that the concept of utility maximization is relaxed. Even though individuals act in order to fulfil their personal goals they do not act as utility maximizers per se. Instead, they only act according to their preferences. Against the background of uncertainty, any action can only be carried out with an expectation of its consequences in mind. Moreover, only performing the action can generate knowledge as to whether the action adds utility or not. This means that there cannot be an optimization towards a global optimum. Since actions are performed in historical time, there is no way to check whether alternative actions could have generated more utility (Holcombe 2014, 31). Moreover, preferences are considered to be unstable; they are both subjective and dependent on prices (Holcombe 2014, 19). This again leads to inherent uncertainty and to complexity at the level of the market.

Uncertainty and variable preferences also implicate a dynamic conception of time. Hence, it is assumed that the decisions people make in the present have direct consequences on future conditions. People make plans based on the knowledge they have in the present and form expectations about the future. The future becomes hard to predict, because unforeseen events occur due to uncertainty; however, individuals have experiences and accumulate knowledge, both of which allow them to develop more or less realistic expectations about the future.

4. Epistemology

Scholars in the tradition of Austrian economics place strong emphasis on the subjective component of knowledge acquisition. Hence it is meaningless to talk about objective phenomena that can be arrived at through sensory experience or impartial observation. Instead, all knowledge related to social phenomena is arrived at through the interpretations of individuals and hence is socially constructed. Hayek emphasized this point by stating that ‘as far as human actions are concerned the things are what people think they are’ (quoted in Hagemann et al. 2010, 257). The contemporary Austrian economist Peter Boettke also states that ‘the facts of social science are what people believe and think’ (see Boettke). Furthermore, Don Lavoie argued that this Austrian understanding of interpretative science fits within the tradition of hermeneutics which focuses on internal understanding and not on external explications (Boettke and Prychitko 2011).

Unlike in other forms of radical social constructivism, this position does however neither imply that scientific truth is considered to be relative, i.e. dependent on the observer, nor that scientific statements cannot be objective. Menger's deductively derived exact laws seek to identify central tenets of economic life, while Mises’ praxeology derives ahistorically valid laws from the axioms of praxeology (see Methodology [Section 5]). By logical reasoning, accordingly, the scientist can understand (verstehen) the kinds of social action that are ‘necessarily true’ and thus can be separated both from historically specific contingencies and from the concrete purpose towards which human action is geared. Indeed, the claim of praxeology to be a value free and universal science rests on its ambition to find the covering laws of the form of human action, such as the law of diminishing returns or the rationality of human actors, while it leaves the specific content of action untouched (Selgin, 1990, 19).

In turn, these universal economic laws are then applied to a broad variety or even to all social phenomena. In his magnum opus Human Action, Mises attempted no less than to develop a science, whose laws would hold irrespective of ‘the place, time, race, nationality, or class’ (Milonakis and Fine 2009, 256). In historical perspective this aim of Mises can be considered to be an extreme case, yet not a deviant one. Members of the Austrian school have time and again emphasized the broad applicability of the economic principle – i.e. rational, cost efficient individual behaviour, which aims at the fulfilment of goals – as well as of analytical concepts like subjectivism and individualism (Blumenthal 2007, 35). Emmanuel Hermann, a less well-known representative of the perspective even argued that the economic principle can be applied to all aspects of human behaviour and even to nature (Haller 1986, 198). Consequently, Austrian economics is driven by its perspective and a certain mode of thought rather than by special interest in a particular social phenomenon.

5. Methodology

Austrian economics’ position in terms of methodological questions in general, and the issue of empirical verification in particular, is rather curious; this is perhaps best explicated by considering the historical context. The strong emphasis on deduction and apriorism as well as the rejection of empirical observations for the generation of new knowledge is probably connected to the role and the statement of Carl Menger in the famous Methodenstreit [method dispute] with the German Historical School.[iv] Friedrun Quaas suggests that Menger’s arguments defending deductive theory against the realist–empirical method, favoured by the members of the Historical School, have led to some ‘confusion’ among later Austrians insofar as they would like to work empirically, but for theoretical reasons take a sceptical stance towards empirics (Quaas and Quaas 2013, 40–41).

In the context of praxeology, it has been argued that statistical inferences cannot play a role in the formulation of theory. This is because the aim of the social sciences is to find an internal – i.e. hermeneutical – access that makes human decisions understandable (Milonakis and Fine 2009, 256; Selgin 1990, 14). Still, the testing of hypotheses using empirical data has been considered to be of scientific value by some Austrians insofar as it can help to falsify a theory when applied to a specific case (e.g. Hayek cf. Hagemann 2010, 222). The falsification of an entire theory by means of empirical testing as postulated by critical rationalism is however rejected. Critical rationalism, which is often associated with the work of Karl Popper holds that one empirical observation that contradicts the theory suffices to prove it wrong. The most famous illustration of this reasoning is that the observation of one black swan falsifies the theory that all swans are white. Modern Austrians have however questioned the validity of theory evaluation according to this principle, amongst other reasons, because they entertain a different definition of what is empirical with regards to the social sciences (for a discussion see Rothbard 1997, in particular 64–66). As a consequence, and in line with their deductive orientation, they hold that only a logical break or an error in theory building can account for such a wholesale falsification.

Another reason that motivates Austrians’ aversion towards statistical and mathematical methods is the ontological complexity of the economy. Kurt Leube argues that such methods can only generate knowledge about entities that are static, non-thinking, not intentionally acting, not learning and not changing, such as stones or water, but under no circumstances about humans (Leube 2010, 263). As a consequence, Austrians often communicate their arguments by verbal descriptions (‘literary economics’ in the words of Don Lavoie, cf. Boettke and Prychitko 2011, 136), as well as by using historical examples for the purposes of illustration. Additionally, thought experiments and counterfactuals form part of the methods of choice (Aimar 2009, 204–205).

Excursus praxeology

Praxeology is a methodological approach that has been developed by representatives of the Austrian school (in particular Ludwig von Mises) and is first and foremost built around the ‘human action axiom’. This axiom states that (only) individuals act purposefully. Praxeological analysis confines itself to asking whether a certain means satisfies the condition to achieve a given end. Questions about the origins of those ends are considered irrelevant for the analysis. By doing so, the perspective guards itself against criticisms that emphasize the existence of intersubjective systems of valuations and needs. Even though people might influence each other as to what their ends are, in the eyes of the Austrians, this does not alter the fact that they act in order to achieve those ends. Even though some proponents of praxeology and of the epistemological and methodological approaches associated with Mises do sometimes pretend to speak for all Austrians it has to be clarified that Hayek, for example, as well as Mises’ disciple Murray Rothbard, distanced themselves from the extreme apriorism and the hostility towards empirics that praxeological analysis entails.

6. Ideology and political goals

Political characteristics often place the Austrian school in close proximity to liberalism and libertarianism and, as a consequence, the perspective is seen as being generally hostile towards the state (Radzicki 2003, 145; Blumenthal 2007, 35). Before the theoretical underpinnings of this position are further elaborated, there are two qualifications that should be noted when assessing this claim.

The first is historical and has to do with the great heterogeneity of political positions. In her historical reconstruction of the perspective, Friedrun Quaas finds attachments to social democratic and reformist politics (e.g. Emil Sax), conservative nationalism (e.g. Friedrich von Wieser) and even Marxism (e.g. Carl Grünberg) among representatives of the first three generations of Austrian economists (Quaas and Quaas 2013, Chapter 1). However, it could be argued that representatives who did not embrace the political ideals of liberalism should not be included in the definition of Austrians. Yet, such a classification would result in the exclusion of, for example, Friedrich von Wieser, one of the constitutive members of the perspective.

The second qualification concerning the link of the Austrians with liberalism is discussed by Randall Holcombe. He points out that if one was to understand the Austrian school as a positive science, there would be no necessary link between the scientific analyses and a liberal political attitude. Positive science in this context means that science just describes the reality as it is and makes no statements about what would be desirable or good. For example, the Austrian school comes to the conclusion that government intervention negatively impacts the market process and decreases welfare. A positive understanding of science now implicates that this has to be acknowledged as a scientific fact, but at first has no further consequences. In a second stage this fact then would be taken subsequently into a process of normative deliberation, where the loss of welfare as something that is considered to be bad from a normative standpoint is evaluated against other normative values that might be associated with government intervention and, based on the weight attached to each of these values, a decision is taken (Holcombe 2014, 107). Holcombe however personally rejects this position and instead argues that the economic and political systems have to be seen as being interdependent. This in turn implicates that a separation of economic and political (normative) decisions is artificial (Holcombe 2014. 108).

The theoretical justification of laissez-faire and pro-market policies that are associated with the Austrian school stems from the conclusion that the market allocates resources efficiently and solves the coordination problem (compare Section 2). The sceptical view on government interventions in the market is derived from the assumption that a technocratic entity – unlike the market – will never be able to understand the complexity of the economic system or to bundle the dispersed information of market participants in an adequate manner. This argument was developed in particular by Mises and Hayek in the course of the Socialist Calculation Debate (Mises 1912, Hayek 1945).[v][5] Their analysis furthermore holds that economic regulation will necessarily lead to unanticipated consequences. This is due to the complexity of the economy, which cannot be fully understood by science. If new problems arise from the results of a regulation, this, according to the Austrians, will induce the government to develop each time new and more regulations to solve problems that arose as a consequence of previous regulations. Hence, a vicious cycle is created, which in the long run will move the economy towards central planning (Holcombe 2014, 108; Hayek 1944).

Apart from the state, there is another political actor that has received strong criticism from the Austrians in the recent past, namely central banks. This critique stems from the conclusions of Austrian Business Cycle theory (described in more detail in Section 7). The negative stance the Austrians take towards central banks is derived from the argument that an interest rate that is too low sends the wrong price signals to entrepreneurs, and this will in turn lead to malinvestments and in the long run to a boom and bust cycle.

Some representatives of the Austrian school have acknowledged a role for the government in securing public goods such as property laws, policing and external defence. A couple of Austrians, like Hayek, even went so far to think about a guaranteed minimum income (Hayek 1944, 124–125). On the other side, more radical members with connections to the tradition of anarcho-capitalism, like Murray Rothbard, have argued that even public goods can be provided by the market in a better way than by the state (Holcombe 2014, 105–106). In conclusion it can however be stated that there is a strong connections between the contemporary Austrian school and the philosophical positions of liberalism.

7. Current debates and analyses

Business cycle theory

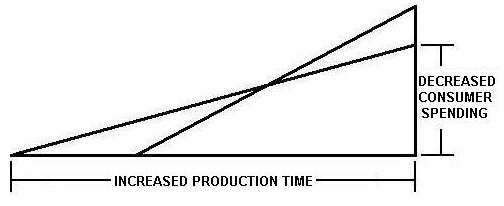

In light of the failure of conventional economic theory in the context of the global financial crisis, representatives of the Austrian school have argued that Austrian Business Cycle (ABC) theory provides a valid alternative that can provide a better explanation of economic crises (Holcombe 2014, 69). ABC theory was first and foremost developed by Hayek, who incorporated into his analytical framework Böhm-Bawerk’s theory of capital and interest and Mises’ monetary theory. Based on this, Hayek develops an endogenous theory of over-investment, which starts from with an economy in equilibrium. This equilibrium, however, gets disrupted when banks grant additional credit to entrepreneurs. If increased credit creation does not coincide with increased savings, i.e. if money creation is carried out, where the price of money (the interest rate) is below the ‘natural’ market rate, then a boom–bust cycle and eventually a crisis will unfold. Seeing low interest rates and interpreting them as a market signal, entrepreneurs will assume that consumers shifted their preferences and want to consume less in the present and more in the future. As a result, according to Hayek, entrepreneurs will invest their additional money, which they obtained as credit, purchasing capital goods, which in turn enable them to build up a (timely) longer and technologically more advanced production process which will generate more revenue. Referring to Böhm-Bawerk’s stages of production, Hayek depicts this in a triangle. In the triangle, making the production process longer makes the production process consume more time, but also it will result in a greater quantity of consumption goods for a lower price at the end of the production process (cf. Quaas and Quaas 2013, 155, 203–204).

Figure 1. Effects of a shifting to a longer and more efficient production process as graphically elaborated by Hayek [vi]

If this process is achieved through increased savings it is unproblematic and results in an overall welfare increase. If the expansion of credit is, however, responsible for the shifts in the production process, there will be a shortage of consumption goods in the present, due to the fact that entrepreneurs, by means of the credits, have more purchasing power compared to consumers and will outbid them in purchasing consumption goods, which they will convert as inputs for their production processes. As a consequence, prices rise and consumption drops. The consumers are thus ‘forced’ to save in the present, so that the entrepreneurs can produce consumption goods in the future. Yet, since the saving is not voluntary but instead only occurs as a consequence of the decision of the banks to expand credit, a wrong price signal regarding the future consumption wishes of the consumers is transmitted to the entrepreneurs. This means that the entrepreneurs will invest in production processes for goods that eventually will not be sold. The investments, hence, turn out to be malinvestments As soon as this becomes apparent, a crisis unfolds. Consequently, consumption goods get scarce, making them relatively expensive, and investment goods are tied up in the wrong production processes. According to ABC theory, the crisis helps to restore the correct price signals, which will then again lead to profitable investments in the right production processes.[vii]

For reasons of space, this explanation of ABC theory stays at a very rudimentary level. Still, in the following section, previous as well as contemporary criticisms of the theory are briefly dealt with. A first fundamental critique of Hayek’s theory was delivered by Piero Sraffa. Sraffa (and others) criticized Hayek’s argument about the natural rate of interest by noting that according to this argument there would have to be a natural rate of interest for all commodities (Quaas and Quaas 2013, 166–169). Another critique came from Joan Robinson, who asked to what extent the rate of interest of a triangle (i.e. a production process) was related to the total stock of capital (and its interest rate). A more recent critique, as well as a summary and more detailed elaboration of these previous criticisms, is provided in Quaas and Quaas (2013). Georg Quaas addresses logical, conceptual and empirical deficits of the theory. One criticism is that if the model is conceptualized arithmetically the difference between a change in the economy that results from voluntary savings versus a change that occurs due to credit expansion can no longer be maintained or observed (218–223). Furthermore, the arithmetical model leads to the seemingly paradoxical result that a more capital-intensive and hence more revenue-yielding production process reduces the productivity of capital (214). From a conceptual standpoint, the linear view on production processes can be questioned, since it leaves out the possibility of circular processes (224). Lastly, the theory also fails to provide an explanation of the latest financial crisis when it is tested against empirical data (244–248).

New Austrians, like Ludwig Lachmann (1986) and Roger Garrison (2001, 2004) amongst others, have responded to some of the criticism and have made attempts to further develop ABC theory.

Entrepreneurship

Another field of inquiry researched by the Austrian school is the theory of the entrepreneur. Recent contributions make a distinction between Schumpeter’s entrepreneurs (pioneering entrepreneurs) and Kirzner’s entrepreneurs (adaptive entrepreneurs). Whereas the former is considered to disrupt and destroy economic equilibria and to introduce revolutionary change, the latter type is adaptive and seeks to develop profitable ways that will bring a disrupted market back to equilibrium (Hall and Martin 2011; Douhan and Henrekson 2007, 4).

8. Delineation: subschools, other economic paradigms, and other disciplines

As already stated in the introduction, perhaps the best way to differentiate between the various strands of thinking within the Austrian school is by incorporating a historical perspective that identifies a total of five generations of Austrians. (A more complete listing of those associated with each of these generations can be found in Section 11).

The first generation, which surrounded Menger (1840–1921), is characterized by the development of subjective value theory, marginalism and marginal utility as well as by a focus on the individual. Additionally, the Methodenstreit with the German Historical School features as a landmark during this generation and Menger defended and further elaborated his deductive theory in the course of this debate. Moreover, monetary theory, uncertainty, knowledge and time played a role in Menger’s work (Blumenthal 2007, 36). The second generation is most of all represented by Friedrich von Wieser (1851–1926) and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1916). As already mentioned, Böhm-Bawerk developed a theory of capital and money that attaches special weight to time. By contrast, Wieser is known for his development of a way in which the prices of production factors are calculated backwards from the (subjective) prices of consumption goods. Wieser did, however, also carry out sociological analyses that are hard to reconcile with the radical individualism of other Austrians (Arena 2010). The third generation of economists that emerged in Austria and had some attachments to the earlier members and their institutions did, however, break with the analytical tradition of individualism as well as with the political tradition of liberalism.

Carl Grünberg (1861–1941) and Othmar Spann (1878–1950) are two scholars that represent this radical break (Quaas and Quaas 2013, 78). Around the same time, Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) built up a new generation of Austrians with a distinct scientific and analytical focus in his Privatseminar. The fourth generation, of whom many had had to migrate to the US as a consequence of the second world war, mainly consists of members of Mises’ seminar. While some of the participants eventually dispersed and took on scientific roles outside the community of the Austrian school, the one member of the seminar that stands out for his importance for contemporary Austrians is certainly Friedrich von Hayek (1899–1992). Together with Mises, Hayek elaborated the interpretation of the Austrian school that the fifth generation of Austrians refer to. This interpretation rests on a strong market liberalism, as well as a focus on knowledge, monetary theory and business cycles. In this context, it should however be stated that there are still some differences between the followers of Hayek and those of Mises. As mentioned in Section 5, there are different attitudes regarding empirics and praxeology. Prominent members of the fifth generation or the New Austrians are Ludwig Lachmann (1906–1990), Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) and Israel Kirzner (1930– ). As to the principal research interest of contemporary Austrians, Richard Neck identifies institutional analysis, macroeconomic theory in particular with regards to deflation, growth theory and questions regarding the emergence of regulations as current fields of investigation (Neck 2014, 123).

Concerning the links of Austrians to other sciences, it can be noted that some members of the school have devoted their later career to social theory and philosophy. Hayek’s career provides an exemplary case for this pattern. The emphasis on hermeneutics that is prominent among the New Austrians and also the proximity to the work of Max Weber that is often mentioned (cf. Kobayashi 2010) place the Austrians, on certain issues, close to the interpretative social sciences.

The centrality of demand and supply, individualism, marginalism and opportunity costs, on the other hand, implies the proximity of the Austrian school to neoclassical economics (Koppl 2006, 239). A similar vicinity is found regarding policy recommendations, which favour the strengthening of the market vis a vis the state. Furthermore, there are ties to evolutionary economics, in particular with regards to the concepts of innovations and of the entrepreneur (Koppl 2006, 237), as well as to psychology, to behavioural economics with regards to the role of knowledge and to New Institutional Economics (Koppl 2006, 235).

9. Delineation from the mainstream

The relationship between the Austrian school and what today is considered to be mainstream economics has historically been marked by tensions. The first two generations of Austrian economists (in particular Menger, Böhm-Bawerk and Wieser) with their focus on methodological individualism, subjective value theory and marginal utility did fit quite well with neoclassical economics and contributed to the development of it. Yet, the emphasis given to issues such as the aggregation of knowledge and a monetary theory of the business cycle (e.g. by Mises and Hayek) has cast them (and their followers) aside of the mainstream (Milonakis and Fine 2009, 245–246). Another aspect that separates contemporary Austrians from the mainstream is their hermeneutic approach to the understanding of human behaviour and the rejection of the econometric methods common in the mainstream. Contemporary Austrians see themselves as part of the heterodoxy in economics, which is understood as part of a newly emerging heterodox, i.e. non-neoclassical, mainstream (Koppl 2006). Yet, as mentioned above, the strongly worded differentiation that New Austrians apply when comparing themselves to the mainstream can also be seen as a conscious strategy of a perspective to present itself as an alternative research paradigm.

10. Institutions

Universities:

Think tanks, Societies:

Friedrich A. von Hayek Gesellschaft

Journals:

Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics

Persons:

1. Generation

- Carl Menger

- Emil Sax

- Robert Zuckerkandl

- Johann von Komorzynski

- Victor Mataja

- Robert Meyer

- Hermann von Schullern Schrattenhofen

- Eugen von Philippovich

2. Generation

- Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

- Friedrich von Wieser

3. Generation

- Carl Grünberg

- Othmar Spann

- Hans Mayer

- Ludwig von Mises

4. Generation

- Gottfried Haberler

- Fritz Machlup

- Oskar Morgenstern

- Friedrich August von Hayek

- Martha S. Braun

- Alexander Gerschenkon

- Alexander Mahr

- Paul N. Rosenstein-Rodan

5. Generation (New Austrians)

- Hans F. Sennhol

- Murray N. Rothbard

- Ludwig Lachmann

- George L. S. Shackle

References

Aimar, Thierry. ‘The Curious Destiny of a Heterodoxy: The Austrian Economic Tradition.’ The Review of Austrian Economics 22, no. 3 (September 2009): 199–207.

Arena, Richard. “Friedrich von Wieser on Institutions and Social Economics.” In Hagemann, Harald, Tamotsu Nishizawa and Yukihiro Ikeda eds. Austrian Economics in Transition. Houndsmille: Palgrave Macmillian, 2010.

Backhouse, Roger E. ‘A Suggestion for Clarifying the Study of Dissent in Economics.’ Journal of the History of Economic Thought 26, no. 2 (June 2004): 261–271.

Blumenthal, Karsten von. Die Steuertheorien Der Austrian Economics: Von Menger zu Mises. Marburg: Metropolis, 2007.

Boettke, Peter J., and David Prychitko. ‘1985: A Defining Year in the History of Modern Austrian Economics.’ The Review of Austrian Economics 24, no. 2 (June 2011): 129–39.

Douhan, Robin and Magnus Henrekson. ‘The Political Economy of Entrepreneurship.’ Research Institute for Industrial Economics. IFN Working Paper No. 716, October 2007.

Haberler, Gottfried. Prosperity and Depression: A theoretical analysis of cyclical movements, 1937.

Hagemann, Harald. “The Austrian School in the Interwar Period.” In Hagemann, Harald, Tamotsu Nishizawa and Yukihiro Ikeda eds. Austrian Economics in Transition. Houndsmille: Palgrave Macmillian, 2010.

Hall, Joshua C. and Adam G. Martin. ‘Austrian Economics: Methodology, Concepts and Implications for Economics Education.’ JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE EDUCATION •Volume 10 • Number 2 • (Fall 2011): 1–15.

Haller, Rudolf. “Emanuel Herrmann: On an almost Forgotten Cahpter of Austrian Intellectual History.” In Grassl, Wolfgang, and Barry Smith eds. Austrian Economics (Routledge Revivals): Historical and Philosophical Background: Volume 18. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 1986.

Hayek, Friedrich A. The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1978 (1960).

Hayek, Friedrich August. Freiburger Studien. Tübingen: J.C.B Mohr, 1969.

Hayek, Friedrich August. ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society.’ The American Economic Review 35, no. 4 (1945): 519–530.

Hayek, Friedrich August von. The Road to Serfdom. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 2001 (1944).

Hayek, Friedrich A. Prices and Production. 2nd edition. New York: Augustus M. Kelly Publishers, 1935 (1931).

Holcombe, Randall C. Advanced Introduction to the Austrian School of Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2014.

Quaas, Friedrun und Georg Quaas. Die Österreichische Schule Der Nationalökonomie: Darstellung, Kritiken und Alternativen. Marburg, Metropolis, 2013.

Lachmann, Ludwig M. “Austrian Economics under Fire: The Hayek-Sraffa Duel in Retrospect.” In Grassl, Wolfgang, and Barry Smith eds. Austrian Economics (Routledge Revivals): Historical and Philosophical Background: Volume 18. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 1986.

Leube, Kurt. “On Menger, Hayek and the Concept of Verstehen.” In Hagemann, Harald, Tamotsu Nishizawa and Yukihiro Ikeda eds. Austrian Economics in Transition. Houndsmille: Palgrave Macmillian, 2010.

Koppl, R. ‘Austrian Economics at the Cutting Edge.’ The Review of Austrian Economics 19, no. 4 (December 2006): 231–41

Milonakis, Dimitris and Ben Fine. From Political Economy to Economics: Method, the Social and the Historical in the Evolution of Economic Theory. Economics as Social Theory. London; New York: Routledge, 2009.

Mises, Ludwig von. The Theory of Money and Credit. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1981 (1911).

Mises, Ludwig von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. 1949.

Neck, Reinhard. ‘Austrian Economics Today.’ Atlantic Economic Journal 42, no. 2 (June 2014): 121–22.

Radzicki, Michael J. ‘Mr. Hamilton, Mr. Forrester, and a Foundation for Evolutionary Economics.’ Journal of Economic Issues 37, no. 1 (March 2003): 133–73.

Rothbard, Murray N. The Logic of Action One: Method, Money, and the Austrian School. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 1997.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Mansfield Centre, Conn.: Martino, 2011 (1942).

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung: Eine Untersuchung über Unternehmergewinn, Kapital, Kredit, Zins und den Konjunkturzyklus, 1911

Selgin, George A, and Ludwig Von Mises Institute. Praxeology and Understanding: An Analysis of the Controversy in Austrian Economics. Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn University, 1990.

Yagi, Kiichiro. “Carl Menger after 1871: Quest for the Reality of Economic Man.” In Hagemann, Harald, Tamotsu Nishizawa and Yukihiro Ikeda eds. Austrian Economics in Transition. Houndsmille: Palgrave Macmillian, 2010.

[i] Hayek, however, also considered a case in which a distortion could lead to the return to the previous market equilibrium (Hayek 1935)

[ii] Joseph Schumpeter, who is often regarded as the founder of evolutionary economics and one of the founders of socio-economics, yet is also associated with the Austrian school, entertained doubts as to whether this function of entrepreneurial innovation could survive in the long run. According to Schumpeter, the increasing size and bureaucracy of businesses and organizations would lead to an ‘obsolescence of the entrepreneurial function’, which alongside other developments would ultimately result in the end of capitalism (cf. Schumpeter 2011 [1942], 131–139; Quaas and Quaas 2013, 85–-88; Milonakis and Fine 2009, 191–-210).

[iii] Böhm-Bawerk undertakes a weighting of the production periods, in which a period more remote in time receives a higher weight. Furthermore, he argues that the average production period can be used to assess the overall efficiency of the production process. See also Quaas und Quaas (2013, 72–73).

[iv] ‚Methodenstreit (German for "method dispute"), in intellectual history beyond German-language discourse, was an economics controversy commenced in the 1880s and persisting for more than a decade, between that field's Austrian School and the (German) Historical School‘.

[v] The adversaries of the Austrians in this debate were Marxist and neoclassical economists. The model of the Austro-Marxist Oskar Lange was mathematically formulated by the neoclassicals Kenneth Arrow and Leonid Hurwicz in the 1960s and offers an analytical solution for the calculation of prices in a socialist system inside the framework of neoclassical economics.

[vi] Graphical illustration by Roger Garrisson: see http://www.auburn.edu/%7Egarriro/b3beyond.htm

[vii] For a somewhat different explanation by Roger Garrison that uses the production possibility frontier (PPF) see https://www.auburn.edu/~garriro/ppsus.htm

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons-Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Assigned course modules

| Title | Lecturer | Provider | Start | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| An Introduction to Political Economy and Economics | Dr Tim Thornton | n.a. | 2022-01-30 | beginner |

Organisations and links

History of Economic Thought Website - Austrian Economics

http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/schools/austrian.htm

Library of Economics and Liberty

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/AustrianSchoolofEconomics.html

Literature

Austrian Economics in Transition

Year of publication: 2010

Palgrave Macmillian

Advanced Introduction to the Austrian School of Economics

Year of publication: 2014

Edward Elgar Publishing