Why We Should Think Twice About Production Functions

Exploring Economics, 2024

1. Introduction

In our first economics classes we are introduced to the production function. It is the cornerstone of neoclassical economics which is often the only perspective covered in undergraduate economics degrees. However, understanding the production function and its limitations is crucial because it has serious implications beyond our lecture halls. For instance, the production function is used to justify how much of the money generated by the sale of output should be distributed as wages to workers versus returns to capital owners. This learning text from students for students explores the production function’s association with neoclassical economists’ narrow view of capital and highlights critiques from non-neoclassical economists.

Section 1 explains the historical development of the production function and its alignment with neoclassical views on capital. Section 2 introduces an alternative perspective from Thorstein Veblen, who argued that capital evolves through complex processes that cannot be encapsulated by a production function. Section 3 examines Robert Solow's attempt to reform the production function by incorporating technological progress. Section 4 discusses the humorous criticism of Solow’s reform. Finally, Section 5 looks at Joan Robinson’s critique, focusing on how the concept of ‘time’ in production functions cannot be compared to ‘time’ experienced in the real world.

2. Production functions and the treatment of capital

A production function in its general form is presented as follows:

This equation indicates that output (Q) is a function (f) of inputs such as capital (K), labour (L), and potentially other factors.

The relationship between inputs and output has intrigued economists for centuries. For example, Adam Smith’s (1776) description of labour specialisation in a pin factory to increase productivity is an early inquiry into this dynamic. We can imagine that economists have had such an abstract relationship in mind when thinking about output and inputs, however, significant controversy has arisen from attempts to express this relationship in an algebraic function and substitute real values for inputs.

In 1817, David Ricardo assumed that labour and capital combine in fixed proportions. As Humphrey (1997) explains, we can imagine this as each labourer having its own shovel. Ricardo illustrated this with a hypothetical example where successive homogeneous doses of these capital-equipped labourers (L) are applied to land of uniform fertility. The first dose produces 180 units of output (Q), the second increased output by 170 units, the third by 160, and so on, with each successive dose contributing 10 fewer units than the previous one. This pattern produced a production function with a quadratic relationship:

In 1842, Johan von Thunen produced a production function with an exponential relationship. As Humhrey (1997) explains, it was expressed in per-worker terms as q = hkn where q is output per labourer, h represents labour productivity (based on the workers strength and quality of the soil), and k is capital per labourer. However, by multiplying each side of the equation by the amount of labour (L) we can rewrite it in a more familiar form:

Lq = Lhkn Multiplying both sides by L

Lq = hLkn Re-arranging terms

Lq = hL(K/L)n Since k = capital per labourer = K/L

Q = hL(Kn L-n)

Q = hL1-nKn

In 1928, neoclassical economists Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas proposed a production function with the following form:

Here, (A) represents technical knowledge, (K) is capital, (L) is labour and α reflects the exponential relationship between capital and labour in producing output.

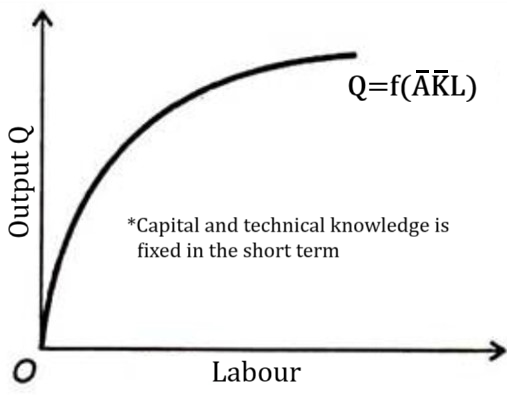

Assuming technical knowledge and capital is fixed in the short term (as indicated by the bars on top of A and K) allows the production function to be graphed, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cobb-Douglass Production Function (Authors’ own)

Adding more labour results in a movement along the horizontal axis. With fixed capital, the increase in output resulting from each additional unit of labour (also called the marginal product of labour) will become smaller and smaller. This is why the slope of the production function becomes flatter. This is referred to as the law of diminishing returns. The same would happen if, instead, labour was the fixed input and capital increased along the horizontal axis.

What you cannot see in this graph is what happens to output if both K and L are increased by one unit each. Output will increase by some amount. It is assumed that output will always increase by the same amount every time both inputs increase by one unit. This is referred to as constant returns to scale.

Measurement of these inputs is an important part of neoclassical production functions. Labour is measured by counting the hours or the number of workers a company employs. Capital would need to be imagined as several identical machines before it can be counted.

All capital is assumed to be homogeneous, even the new ones a firm could purchase, otherwise, it would create chaos when trying to draw the curve and calculate the difference in output (Q). If capital becomes more expensive or scarce, firms can adjust their mix of capital and labour to optimise production. Assuming that capital is homogenous has the convenient result that the rate at which one input is substituted for the other will always be constant.

A production function is based on an imaginary, almost toy-like situation. Yet, it is used to justify how much of the money generated from the sales of output (Q) should be distributed to labourers as wages versus return to owners of capital.

Students often wonder how someone can even think of a homogenous “unit” of capital. For instance, how many “units” of capital are in one laptop? Is a pen also a type of capital? How about software? Shouldn't the production function account for how better types of capital allow for higher output? Such issues of defining and measuring capital are important and have sparked several controversies centred on (1) how we think of capital in the context of industrial capitalist societies, (2) the adequacy of equilibrium as a method for analysing the processes of capital accumulation, and (3) the influence of ideology and vision in fuelling controversy when the results of simple mathematical models (such as the Cobb-Douglass production function) are not robust enough to perform well under a variety of conditions (Cohen, 2014: p.1494). Economists at MIT in Cambridge, USA, generally preferred the elegance of the mathematical approach, while those from Cambridge, UK, favoured more nuanced views on capital and production.

Another question students often raise is why natural resources and land are not included in the production function as an additional type of input. This, however, would be too difficult. Who the owners of such resources are and how their value changes will complicate how money from the sale of output is distributed. Furthermore, this type of equation cannot capture the role that land and natural resources play in production regarding negative externalities such as environmental degradation and resource depletion. Oversimplifications are often the only way to get the mathematics to work as intended. Therefore, the production function remains silent on this issue. Instead, it is studied separately for instance by environmental economists and Georgist economists. However, since natural resources are central to production and economic development, and should never be treated as a separate issue, it pits neoclassical economists against these other economists.

This emphasis on oversimplified situations first became popular in the late 1800s when a growing group of economists sought to study the economy like physicists studied the physical universe. This approach required isolating the economy from its broader social and ecological interactions. Questions of how things evolve, connect and emerge were pushed aside while mathematical equations, similar to those used in physics at the time, were used to explain what remained. These economists proudly presented this as the “pure theory of economics” (Walras, 1874). Today we know that this is more accurately referred to as the neoclassical theory of economics.

In this theory, individuals are characterised merely by their preferences for the output produced by firms. The only thing that workers do in life is use their earned wages to satisfy these preferences. Capitalists, on the other hand, spend money on hiring labour (L) and renting capital (K) and this money comes back to them as the labourers spend what they earn. Kalecki (1971) sums this up by saying that capitalists earn what they spend and workers spend what they earn. With these, so called, ‘rational representative’ people and businesses in mind, curves were drawn up that describe the level of utility received from various bundles of goods, and the mathematics kicked in. It resulted in the other models we study in first-year economics textbooks, for example, demand curves, supply curves, equilibrium points, etc.

The story goes a bit like this. When a firm has a fixed amount of capital and can vary its labour, each labourer works with the capital at their disposal to add a marginal product to total production. This marginal product will become smaller and smaller as more labourers join. A firm will hire more workers as long as this marginal product results in a profitable outcome. This allows the identification of a point where the wage (cost of adding a worker) equals the marginal labour productivity (benefit of adding a worker).

So just as consumers are said to maximise their utility which can be identified and associated with values, firms are said to use the production function based on units of capital and labour to maximise profit. Both parties are assumed to act independently with perfect knowledge of their utility and expected profit. In this way, a perfect equilibrium plays out in society. The production, consumption, and value of goods and services are understood in terms of imaginary lines (also known as supply and demand curves) which meet at an equilibrium point that indicates the most efficient output quantity and wage.

As we see in the next section, this oversimplified view of production, and especially of the role of capital, have been criticised by non-neoclassical economists.

3. Thorsten Veblen's concept of capital

Thorstein Veblen, a founder of institutional and evolutionary economics, started a long-standing critique of neoclassical production functions, particularly their treatment of capital. In his 1898 paper “Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?”, Veblen argued that capital, individuals and institutions co-evolve over time. Then, in 1908, he applied this perspective to challenge the assumptions underlying neoclassical production functions.

Veblen’s view of capital is grounded in two key claims: one, individual action makes up the institutional landscape while it is also shaped by it, and two, individual action interacts with the materials available to humankind causing technological evolution. The capital produced from this process is therefore a combination of the materials as well as the individual’s insights and appreciation for how these materials can be used. Over time, advances in capital foster new “prevalent habits of thought” (Veblen, 1908, pp. 387), which, in turn, enable new forms of productive activity. This evolving relationship highlights the inadequacy of static models like the neoclassical production functions in capturing the complexity of capital.

According to Veblen’s explanation, capital cannot be measured solely as a stock of physical goods (Davanzati & Pacella, 2017, pp. 134). Consequently, deriving a mathematical function for the marginal productivity of labour becomes impossible. The analysis of a decreasing marginal product of labour against a fixed stock of capital, as discussed in Section 2, is therefore irrelevant and has no practical application. Since capital cannot be measured, the equality between real wages and marginal labour productivity does not exist and cannot be used to prove that the “equilibrium wage” is a fair wage (Davanzati & Pacella, 2017).

Even if capital could be measured, the marginal productivity of labour would remain indeterminable in real-world contexts. For example, in a software company hiring additional coders, the effectiveness of capital lies not only in the physical computer but also in the coder’s unique skills and creativity. This interplay makes it evident that the individual labourer’s contribution to production cannot be neatly isolated or quantified.

Veblen laid the foundation for an alternative understanding of production (Cohen, 2014). He claimed that processes resulting from capital’s modern use in firms could at times be inefficient and unfair, contrary to popular belief that capital managed by private firms is always more efficient and more fair than collective management. A similar conclusion was reached by Elinor Ostrom (1990) in her empirical research. Veblen presented two points to support his claim (Davanzati & Pacella, 2017). The first addressed opportunities for capitalist control of the production process and while the second addressed capitalist control of everything capital represents socially.

As to his first point, Veblen stated that “the ownership of the capital goods affords a discretionary power of misdirecting in the industrial process and perverting industrial efficiency, as well as inhibiting or curtailing industrial processes and their output...” (Veblen, 1908: p.108). A level of scarcity is maintained through a “conscientious withdrawal of efficiency,” or in other words, trying to produce the quantity that takes advantage of economies of scale only as far as that quantity keeps the product scarce enough to assure the highest possible return. In Veblen’s words, the “earning-capacity [of capital] is determined by what the traffic will bear” (Veblen, [1923] 1967, pp. 68), that is to say by “curtailing production to such an amount that the output multiplied by the price per unit will yield the largest net aggregate return” (Ibid, pp. 68). This is an injustice to society and a “sabotage of industrial efficiency” (Ibid, pp. 285). This profit-maximising quantity maximises producer welfare, minimises consumer welfare, and society becomes unequal. The incentives that create this artificial scarcity stem from the capitalisation process itself and are upheld by an economic and legal order (Cohen and Harcourt, 2023).

As to Veblen’s second point, he recognises that technology-driven emergence of new habits of life and thought translates into institutional change, which then affects technology; so that when institutions change, technology changes too (Cordes, 2007). The neoclassical view of capital as a stock contained in a firm’s physical and intellectual assets is only one part of an interconnected situation where the firm that controls capital also controls a society’s institutions (Davanzati & Pacella, 2017). The individual and the social aspects of knowledge are connected in a way where the “social environment and its collective experience” provide the means and stimulus to individual learning (Hodgson, 2004, pp. 183). Veblen’s warning is especially relevant today, as a small number of technology firms who own powerful capital based on the collective knowledge of individuals (and their data) are able to shape the direction of society.

This complex relationship between capital and other inputs were ignored by neoclassical economists. Instead, their focus shifted to how technical advances in capital impact total output.

4. Robert Solow tries to isolate ‘technical change’ in production

Robert Solow was a neoclassical economist who wanted to know which portion of total output (Q) in the USA economy was due to increases in inputs (K,L) and which portion was due to increases in technical progress (1957). He started by taking the usual aggregate production function and adding a new variable, t, which was meant to represent technical progress that happens over time:

However, he explained that, in the function, t was a type of “catch-all” variable that captured any shifts in output other than those directly resulting from changes in the number of inputs (K, L). Thus, in reality, it included not only technical progress but also any other reason that could be responsible for a speed up or slowdown of production (for example when the labour force becomes more educated or new incentives are put in place for reaching production targets). Solow interpreted the notion of “technical change” very broadly.

He continued by assuming that technical change was neutral, in other words, new types of capital did not alter the marginal rates at which capital and labour are substituted for each other in producing output. He also imagined these changes taking place without increasing the total amount of capital, as old-fashioned capital is replaced by the latest models, so that the capital-labour ratio did not have to change. Although he knew these assumptions raised problems in defining and measuring capital, he went ahead anyway.

Since these assumptions meant that t simply increases or decreases the output attainable from the existing inputs, it could now be treated as a simple variable and the following mathematical re-arrangement of the production function was now allowed:

Q = A(t) f (K, L) (5)

Note that A (t) is a neutral multiplier acting to shift the function.

Solow also assumed competitive factor markets where L and K are paid their marginal product. Although he said nothing about returns to scale, he noted that “an amusing thing happens here” (Solow, 1957, pp. 316), if all factor inputs were classified either as K or L, then the available figures always show the share of capital (wK) and the share of labour (wL) adding up to one (Solow, 1957). Since he has assumed that factors are paid their marginal products, the mathematics being what it is, he was able to just as well assume that the function is homogeneous of degree one, or in other words, that the function exhibits constant returns to scale.

By deriving equation 3 with respect to t and then dividing each term by Q so that Q/L = q stands for output per unit of labour, and K/L = k stands for capital per unit of labour, Solow was able to write the function in the form of Equation 6, below.

![]() (6)

(6)

Note that dots indicate derivatives and that

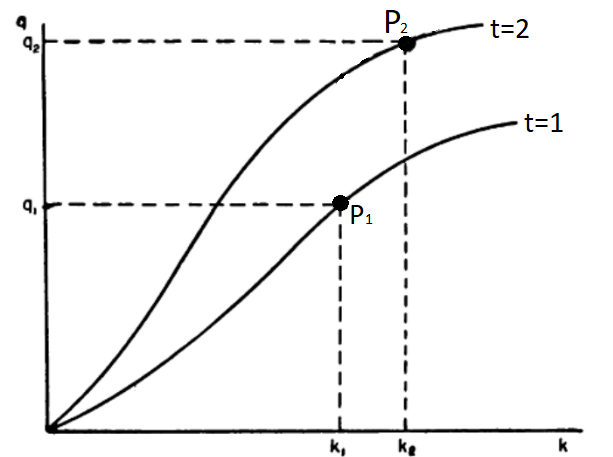

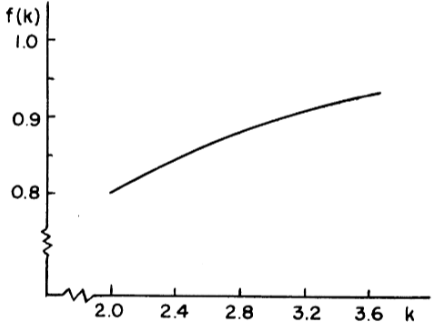

Figure 2: Composite Production Function q = A(t) f (k) (Solow, 1957)

The above production function is completely represented by a graph of q against k, showing neutral shifts in technical progress and constant returns to scale. An increase in output, for example from P1 to P2, is compounded by a movement along the curve and a shift of the curve. However, if the shift factor for each point of time can be estimated, the observed points can be corrected for technical change to reveal the underlying production function.

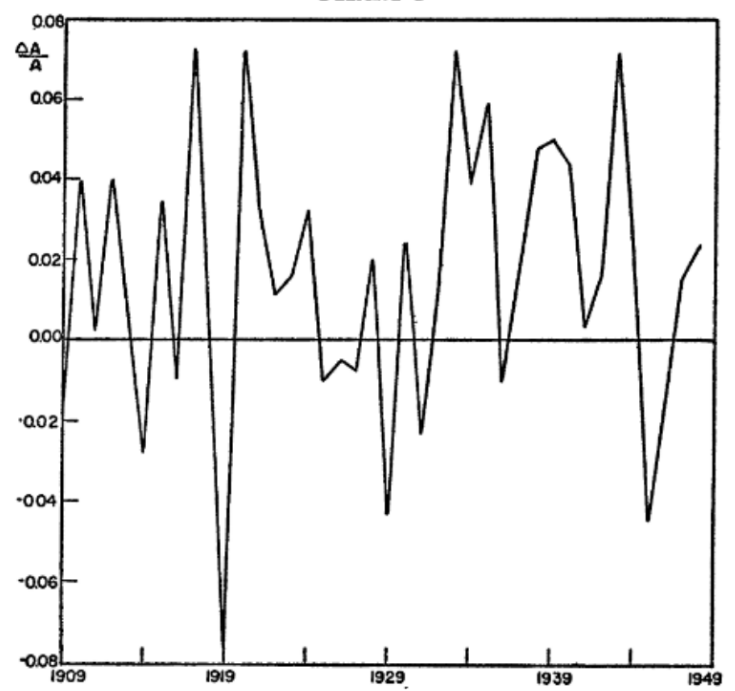

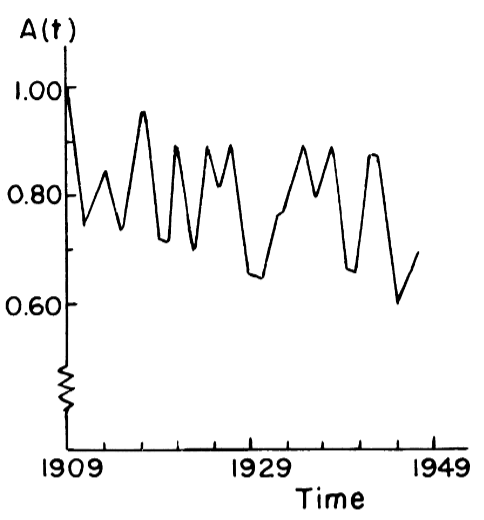

All Solow needed now was time series data to be able to isolate a series for technical progress. Towards this end, he gathered real output data for the USA between 1909 and 1949. For q, he used a time series of real private GNP per labour hour. For k, he used Goldsmith’s (unpublished) estimate of capital goods in existence corrected by a ratio representing idle resources. For the share-of-capital series, he “pieced it together from various sources and ad hoc assumptions” (Solow, 1957: p.314). Solow ran the data through Equation 6 and calculated the technical change time series (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Technical Change Time Series (Solow, 1957)

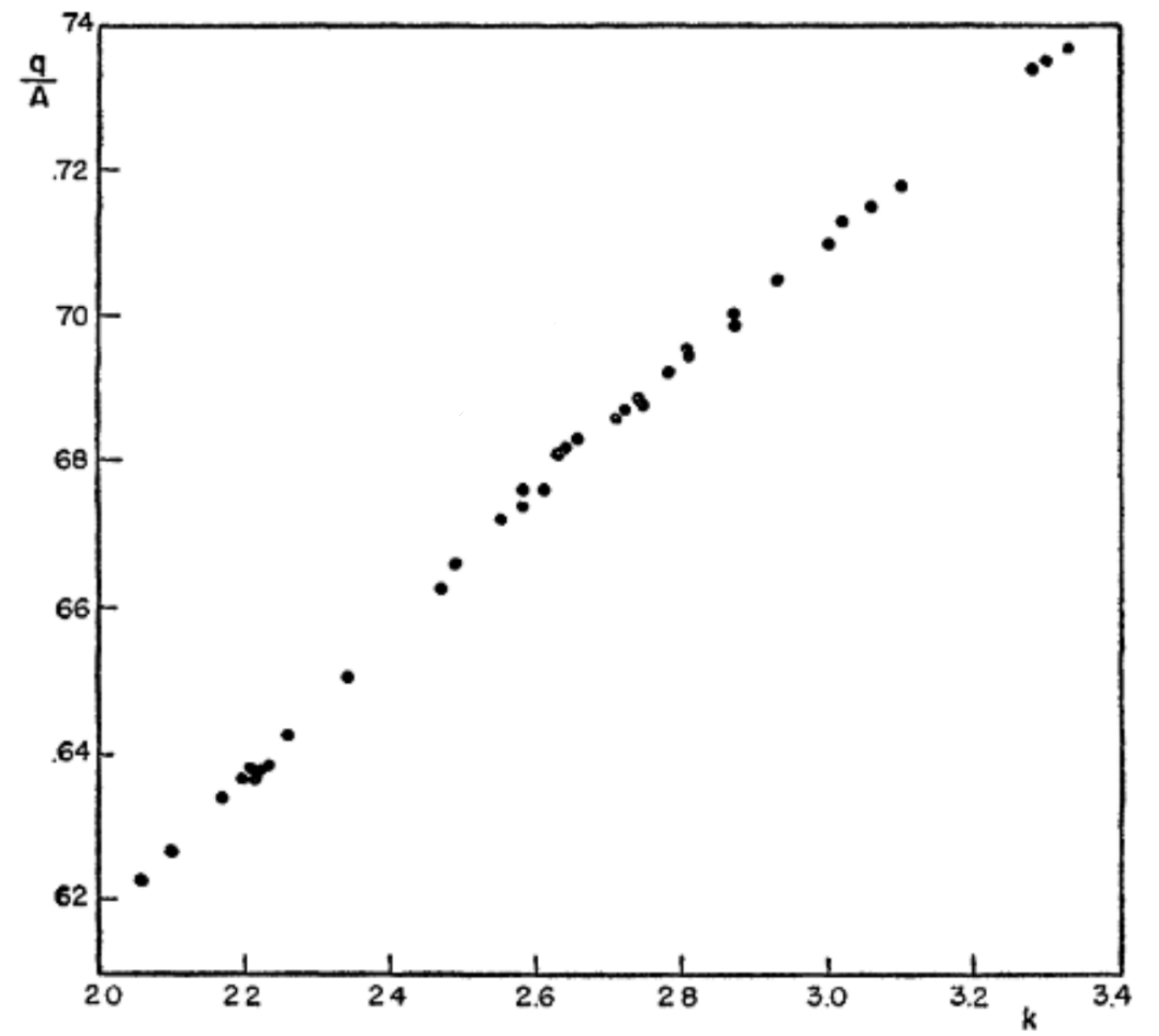

Figure 4: Underlying Production Function (Solow, 1957)

The time series in Figure 3 exhibited no relationship with k (the ratio of capital to labour), so Solow concluded that technical change (shifts in the aggregate production function) was indeed neutral in the US between 1909-49. He also concluded that the output per labour hour approximately doubled, the cumulative upward shift in the production function was about 80%, and that about one-eighth of the total increase is traceable to increased capital per labour hour, while the remaining seven eights can be attributed to technical change.

To map the underlying production function, Solow divided both sides of the composite production function equation by A(t) to get q = f(k). Figure 4 shows a scatter of q/A against k. Solow remarked that the fit was remarkably tight and that there was a noticeable curvature in the row of points. He concluded that the curvature implied diminishing returns to scale as k increases along the horizontal axis, and that the points representing the underlying production function best fit a Cobb-Douglas production function.

One of this fellow neoclassical economists at MIT conceded that the requirements under which the production possibilities of a technically diverse economy could be represented by an aggregate production function are far too stringent to be believable (Fisher, 1971), yet the empirical data matched the Cobb-Douglas production function with its constant returns to scale and aggregate marginal productivity theory of distribution remarkably well.

5. Criticism of the Solow Production Function: Anwar Shaik’s HUMBUG production function

The HUMBUG was a paper by Anwar Shaik that criticised how economists such as Robert Solow represented economic data with production functions, particularly the Cobb-Douglass production function (Shaik, 1974).

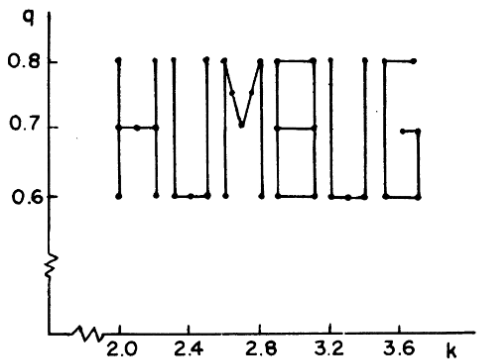

In 1974, Anwar Shaik set out to prove that the only reason that the Cobb-Douglass production function with its constant returns to scale (CRTS) seems to represent the data so well is not due to some result of production as assumed by Solow, but rather due to a mathematical rule that would be true in general of data representing constant shares. To prove this, Shaik placed made-up points inside Solow’s graph which spelled the word “HUMBUG” (see below). Humbug is defined as “false talk” or “something which is made up”.

Figure 5: Humbug Economy (Shaik, 1974)

Running these points for k and q along with the same capital share as Solow’s US data through the same process as Solow did, Shaik isolated the shift parameter A(t) and the underlying production function as shown below. Similarly, Shaik’s result also indicated noticeable curvature.

Figure 6: Humbug Technical Change series (Shaik, 1974)

Figure 7: Humbug Underlying Production Func. (Shaik, 1974)

One could have the remarkable conclusion that even the implausible Humbug data is extremely well represented by a Cobb-Douglas production function having CRTS, neutral technical progress, and marginal products equal to factor rewards. It seemed like the apparent empirical success of the Cobb-Douglas function having “correct” coefficients was perfectly consistent with wide varieties of data, and could not be interpreted as supporting aggregate neoclassical production and distribution theory.

It turns out that, under fairly reasonable conditions, such a function will also seem to possess “marginal products equal to respective factor rewards”, thus seeming to justify neoclassical aggregate distribution theory (Shaik, 1974: p.116). These propositions are mathematical consequences of constant shares. The puzzling uniformity of the empirical results was in fact due to an independent law of algebra, not to some law of production.

Readers interested in a detailed explanation of the laws of algebra behind the transformation of Solow’s and Shaik’s data may refer to Shaik’s 1974 paper.

6. Joan Robinson’s thoughts on Neoclassical models of inputs and outputs

Joan Robinson (1980), a key figure in the Cambridge Capital Controversy, warned how our relations to an event in the past and an event taking place today are radically different. She criticised the construction of neoclassical style models such as the Cobb Douglass production function that trace the effects of a change in a particular event over time while keeping all else constant. She dismissed such efforts as “idle amusement” and argued that it is futile to construct models where “technology can be represented in a single system of equations” (Ibid. pp. 223-224).

Robinson (1980, pp. 228) urged economists to “give up the search for grand general laws” such as the marginal productivity of capital and equilibrium output found in production functions. Instead, she advocated for developing hypotheses about the world we are living in, a world where productive capacity evolves due to technical change, including cumulative changes in how the labour force operates.

Robinson explains that ‘time’ is treated as logical time in most models, which is different from actual historical time. The logical time is what flows between two static points of equilibrium that we observe from the very first models we learn. It does not make sense to hold it to a clock or a calendar because it can neither be measured nor waited out. This produces a difficulty in relating it to the real world described above.

Based on this, Robinson did not believe neoclassical models could predict steady states of equilibrium in the future. She argues that the future is foreseen on the basis of the past. When using logical time for modelling, or predicting, we blur the lines between the actual past and future. Put simply, the assumption is that history, when it was relatively less dramatic, will repeat. However, if we think about it, there is always some drama happening, and never has there been a point in time where the economy could be labelled as ‘normal’. Robinson asks, how we can predict a convergence to normality (equilibrium) based on the past, if we cannot point to a normal state in the past?

Given this colourful mess, can we really reduce the individual and all of their dynamic needs to a “representative consumer”? Can we reduce the course of time to a couple of lines in a graph? Can we reduce our economies to a bunch of models in a textbook? Joan Robinson would think twice about this, and so should we.

References

Boulton, J. 2010, ‘Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science? Thorstein Veblen With an introduction by Jean Boulton’, Emergence: Complexity and Organisation, vol. 12, no. 2. Available at: https://www.embracingcomplexity.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/why_is_economics_not_an_evolutionary_science_may3.pdf (Accessed: 28 February 2024).

Cobb, C. & Douglas, P. "A Theory of Production," American Economic Review, Vol. 18 (Supplement) (March 1928), pp. 139-65.

Cohen, A. J. 2014, ‘Veblen Contra Clark and Fisher: Veblen-Robinson-Harcourt Lineages in Capital Controversies and Beyond’, Cambridge Journal of Economics vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 1493–1515.

Cohen, A.J., & Harcourt, G.C. 2003, ‘Retrospectives Whatever Happened to the Cambridge Capital Theory Controversies?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 199–214. doi: 10.1257/089533003321165010.

Cordes, C. 2007, ‘Turning Economics into an Evolutionary Science: Veblen, the Selection Metaphor and Analogical Thinking’, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 42, no. 1. pp. 135-154. Doi: 10.1080/00213624.2007.11506998

Davanzati, G.F., & Pacella, A. 2017, ‘A Capital Controversy in Early Twentieth Century: Veblen vs. Clark’, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 118-136, doi: 10.1080/00213624.2017.1287499

Fisher, F. M. 1971, “Aggregate Production Functions and the Explanation of Wages: A Simulation Experiment” Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 305-325.

Hodgson, G.M. 1998, ‘On the Evolution of Thorstein Veblen’s Evolutionary Economics’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 415-431. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23600432 (Accessed: 28 February 2024)

Humphrey, T. 1997. Humphrey, “Algebraic Production Functions and their Uses before Cobb-Douglas”, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Vol. 83. No. 1, pp. 51-83. Available at http://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedreq/y1997iwinp51-83.html

Kalecki, M. 1971, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ostrom, E. 1990, Governing The Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom.

Robinson, J. 1980, ‘Time in Economic Theory’, International Review for Social Sciences, vol. 33, issue. 2, pp. 219-229, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1980.tb02632.x

Sraffa, P. 1960, ‘Production of Commoditied by Means of Commoditied’, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Shaik, A. 1973, ‘Laws of Production and Laws of Algebra: The Humbug Production Function’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 115-120, doi: 10.2307/1927538

Smith, A. 1776, An Inguiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Oxford University Press, United Kingdom.

Solow, R 1957 ‘Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 39 no. 3, pp. 312-320, doi: 10.2307/1926047

Veblen, T. 1898, ‘Why is economics not an evolutionary science?’ Quarterly Journal of Economics. vol. 12, issue 4, pp 373–397, doi: 10.2307/1882952

Veblen, T. 1899, Theory of The Leisure Class, Macmillan, New York.

Veblen, T. 1908 ‘On the Nature of Capital: Investment, Intangible Assets, and the Pecuniary Magnate’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 104-136, doi: 10.2307/1883967

Veblen, T. 1921. The Engineers and the Price System. Kitchener, Canada, [Replublished 2001].

Veblen, T. 1923. Absentee Ownership: The Case of America, Boston, Beacon Press, [Republished 1967]

Walras, L. 1874, Elements of Theoretical Economics or the Theory of Social Wealth. Translated and edited by Walker, D. A. & van Daal, J. (2019), Cambridge University Press, New York.