The Political Economy of Extractivism

Exploring Economics, 2025

The Political Economy of Extractivism - Natural Resource Rents, Inequality, and Challenges Ahead

Hannes Warnecke-Berger, University of Kassel, www.extractivism.de, hwarneckeberger@uni-kassel.de

Jan Ickler, University of Kassel, Department of International and Intersocietal Relations, j.ickler@uni-kassel.de

Summary: Extractivism is a development model based on exploiting and exporting raw materials. It is fundamental to reproducing entire societies, mainly in the Global South, while generating manifold dilemmas. This text situates extractivism within the broader landscape of global economic asymmetries, emphasizing the role of rents—excess revenues generated from resource extraction due to international price differentials—as a central analytical lens. Rents not only shape economic structures but also influence political institutions, social dynamics, and power relations, reinforcing dependency on raw material exports while obstructing structural change. By examining historical trends, we highlight how extractivist economies have remained entrenched in global inequalities despite attempts at industrial diversification and policy interventions. In doing so, we engage with competing theoretical perspectives, from neoclassical trade models to Marxist and dependency approaches, to analyze specialization patterns and their consequences. The specialization of natural resource exports exacerbates global inequality and leads to various problems, including fluctuating export prices, ecological damage, and technological dependence. Despite known risks, many political actors continue to promote extractivism as a pathway to development, viewing it as vital for national sovereignty and economic growth. In this context, we discuss the potential for industrial policies and rent management to facilitate development while recognizing the political constraints imposed by rent-seeking coalitions. Finally, the paper considers the future of extractivism in the context of the global energy transition, arguing that the "green" economy risks perpetuating unequal specialization and reinforcing global disparities despite its sustainability ambitions.

Introduction

Natural resources[1] play a vital role in the global economy. Without the steady consumption of hydrocarbons, metals, and grains, contemporary industries and societies on this planet would likely collapse (Barbier, 2019). Natural resources make up around 20 percent of total world trade (UNCTAD, 2023b), and their production is a colossal business, spanning multiple countries and incorporating firms from different sectors. Natural resources have to be located, extracted, and exported. Most countries producing natural resources are located in the Global South. For them, exploiting and exporting natural resources has become a fundamental development model. In this context, the concept of ‘Extractivism’ has emerged to encapsulate this development model with all its social, political and economic impacts.

Discussions on extractivism are in vogue and have also entered the political arena: Alongside political activists, NGOs, and social movement leaders, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz picked up the term recently and emphasized searching for alternatives to extractivism in the global south.[2] However, extractivism is not only a political catchphrase but a contested concept enveloping multiple ongoing debates in political economy. It connects the role of natural resources in the global economy with strategies of governments, economic sectors, and social classes in national settings, as well as social movements and processes of exclusion on the local level.

Extractivism poses significant risks, harms the environment, and incites social conflict (Chagnon et al., 2022; Dietz & Engels, 2017). Despite these well-documented issues, powerful political actors in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East continue to advocate for resource exports to achieve national development, economic sovereignty, and self-determination (Ickler & Ramos Padrón, 2025). Extractivism, therefore, refers to a political ideology that links raw materials to development. Over the decades, both elite-oriented as well as progressive, mass-oriented political coalitions have championed this development myth as a driving force for growth and prosperity (Warnecke-Berger et al., 2023). In summary, extractivism is a development model that shapes entire societies and lifestyles, having a profound impact on everyday life. This connection between political struggle, contemporary challenges, historical dynamics, and lived experiences gives the concept of extractivism its significance. A political economy of extractivism has to account for that richness and seek approaches to analyze these different phenomena.

In this text, we want to outline the program of a political economy of extractivism. In this perspective, extractivism unfolds on various levels, each with its own theoretical implications. This is why we begin by providing an overview of the research landscape. In doing so, we advocate for an approach grounded in political economy that emphasizes the surplus generated by extractivist activities: rent. We then investigate the underlying processes driving extractivism, emphasizing its impact on entire societies. In the second section, we will analyze the international dimension of extractivism and discuss essential dynamics within the global economy, exploring why extractivism persists despite widespread recognition of its significant challenges. Finally, this text addresses how extractivism is evolving in response to current political and economic events and how the political economy of extractivism aids in understanding these phenomena.

Extractivism in Theory: Strategy, Model or Social Order?

The definitions of extractivism vary. The term originated from social struggles in Latin America during the 1990s. This decade was marked by debt crises and neoliberal structural adjustments that left the continent with little more to offer than unprocessed raw materials. Consequently, disputes over the distribution of revenues and earnings of extractivist activities arose. In the eyes of social movements and the left opposition, the fruits of extractivism should benefit not just the elite but also the broader public, especially the poor. During the so-called “Pink Tide” in Latin America between 1998 and 2017, newly elected left-wing governments in Venezuela, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, and Ecuador leveraged high export prices to launch development programs and implement welfare initiatives. From today’s perspective, this “neo-extractivism”, despite some successes, has fallen short (Burchardt & Dietz, 2014; Svampa, 2019). In Latin America, many countries are still dependent on resource exports, and governments have failed to initiate structural change toward overcoming extractivism.

Eduardo Gudynas (2020) argues that extractivism exists if a country has high extraction volumes, minimal processing activities, and over 50 percent of exports are made up of natural resources. This perspective also emphasizes severe environmental degradation and social exclusion caused by mining and agricultural monocultures. Many authors link extractivism to Western colonialism, seeing it as a product and legate of historical exploitation that perpetuates resource dependency in colonized regions. (Veltmeyer & Petras, 2014). Others argue that extractivism is a normal pattern of export specialization that follows resource endowments, with resource-rich countries focusing on extraction while others produce manufactured goods (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2013). Technological advances and the rise of transnational mining companies have intensified extractivism and its social, economic, and environmental impacts, leading to increased local and global contestation. Areas of extraction often become “zones of sacrifice,” providing little benefit to local communities (Bruna, 2023). Some authors believe we now live in a state of “hyper-extractivism,” making it a primary driver of ecological change (Shapiro & McNeish, 2021). However, as the concept expands to encompass many phenomena, its definition becomes increasingly blurred and unclear.

We argue that extractivism must be analyzed from a political economy perspective. Within extractivism, economic (e.g., production, extraction, exports) and political logics (e.g., rent-seeking, clientelism, and populism) are linked. We contend that extractivism refers, first, to the exploitation, appropriation, commodification, and export of raw materials. Second, extractivism denotes the impact of this economic structure on political institutions, social dynamics, representations, ideologies, and practices. Extractivism, thus, involves resource exploitation that shapes societal organization and shared understandings through appropriation, distribution, and eventually exclusion. The entry point for this analysis is rent. (Differential) Rents are revenues from exports that accrue because of international price differentials. Rents are appropriated and distributed by various actors, first and foremost by the state. However, rents tend to shape entire societies economically, politically, and culturally. We argue that the concept of extractivism should only be applied to those social formations that rely, either directly or indirectly, on rents (Cerioli & Warnecke-Berger, forthcoming). A definition of extractivism rests in political economy and thus comprises the following aspects:

First, there is a difference between extraction and extractivism. The extraction of raw materials is historically ubiquitous, and virtually all societies in the world extract raw materials from their territories, at least to a certain extent. Extractivism, in turn, signifies that economies specialize in extracting and exporting raw materials. For their social reproduction, these societies depend on the revenues from exporting natural resources. The economic processes behind extractivism order society and even shape economic sectors and societal segments that are not directly related to extraction. Therefore, we reserve the term extractivism to those societies where the surplus structure is marked and even dependent on the inflow of revenues from extraction. (Warnecke-Berger, 2025b).

Second, the key factor in extractivism is rent. Revenues from extraction are specific: in addition to the expenses for labor, technology, and intermediate goods, they usually contain a significant share that cannot be traced back to these expenses. We call this part rent. (Differential-) Rents are based on the fact that production prices do not converge internationally, and countries with lower-cost production options can appropriate excess revenues. This happens because, although they produce more cheaply, their goods sell for the same price on the world market as their competitors. The following data illustrates this process. Saudi Arabia produces a barrel of oil for about $10. Norway, however, has to spend $45 to produce a barrel of oil. Since global demand for oil is very high and oil is sold on international markets under competitive conditions, the average price of crude oil has stabilized at around $65 per barrel since 2000. Norway also makes a profit. Saudi Arabia can appropriate the difference between the marginal production costs in Saudi Arabia and those in Norway as a (differential) rent. This rent, which in the example is $35, accrues to Saudi Arabia for no apparent reason other than having lower marginal production costs. This rent arises out of the necessity for both countries to produce the same product and sell it at a similar price. The decisive factor in this case is the structure of the world economy and the divergent production prices. In this case, no (market) force equalizes production costs.

Rent accrues in agriculture, for example, in global wheat or soy production and oil, copper, or lithium production. However, rents also arise in global financial markets and manufacturing sectors. In most cases, however, they disappear after a short time because adjustment mechanisms take effect that align production costs internationally. Rents can also be neutralized politically by actively undermining their impact on politics and society through innovative policies. (Bresser-Pereira, 2020). However, raw materials are particularly prone to rents because their extraction is location-bound, uses globally available technology, and can be monopolized by a few companies. Rents account for a considerable share of world trade in commodities. On average, the share of (differential) rents in the value of world trade in raw materials has amounted to just over 50 percent since 1970. At the same time, the annual average of the rents accruing from trade in raw materials alone can be estimated at 15 percent of the value of total world trade in recent decades; they thus currently reach approximately the value of France's gross domestic product (Warnecke-Berger, 2025a).

Third, rent creates windows of opportunity for a variety of actors. As a remarkable source of income that arises in the world economy, they are not tied to the compulsion of market forces. They can be invested and spent on whatever means: social reforms, industrial prosperity, or self-enrichment. Political action toward structural change seems unlikely (Storm, 2015). Within the societies that appropriate these rents, they are both a curse and a blessing (Smith & Waldner, 2021). Political actors can just as quickly transform rents into loyalty, dependencies, system maintenance, or repression and exclusion. Societies whose social reproduction depends on rent have one crucial characteristic: they are not socialized through the market (Elsenhans, 1996). Social positioning within society is not based on economic achievement, investment, and labor productivity; instead, the position of individuals depends on political access to rents and, thus, on membership in relatively closed social groups.[3] This has an enormous influence on the importance of politics because this access to rents shapes the behavior of political groups and broader sections of the population.

Fourth, the amount of rent in many extractive societies is insufficient to cover the entire population's needs. A political struggle for the appropriation and use of rent arises, and individual social actors must form coalitions. Usually, the coalitions that control rent develop political options to block far-reaching transformation processes to maintain their privileged status quo. Thus, a dynamic between elite-oriented and mass-consumption-oriented development strategies emerges from the distributional conflicts over rents. Rent societies, therefore, are dynamic and impacted by social change. However, this change does not automatically transform the entire development model in a structural way. Instead, on closer inspection, rents turn out to be seductive (Warnecke-Berger & Ickler, 2023). Even development-oriented groups repeatedly favor rent-seeking strategies that even shape mentalities and cultural practices. As a result, rents are usually glorified as a development myth because many governments often equate the appearance of additional financial resources with development without, however, creating economic alternatives to rent sectors (Warnecke-Berger et al., 2023).

These four dimensions allow conceptualizing extractivism as a development model sui generis based on the inflow of rents from the specialization in raw material exports, the appropriation of these rents through a coalition in power, and the out-competition of distribution against production as a structuring mechanism within the domestic sphere. This insight allows for tracing economic and political developments in extractivist societies. The next section builds on that and explains how extractivism originated historically and is connected to a global economic order.

Extractivism in Practice: Persistent Sovereignty, Dependency, or Unequal Specialization?

Historically, raw materials have shaped trade routes connecting societies across vast distances and extended periods. They have played a key role in the rise and fall of empires and continue to influence the dynamics of the global economy at an astonishing pace. Since at least the early 19th century, however, global trade in raw materials has significantly contributed to an increasingly unequal international division of labor. This inequality divides countries into raw material suppliers and buyers, considerably affecting their development potential. Only a few countries have established the national and international conditions needed to enhance their positions in this imbalanced world economy and break free from the cycle of extractivism. In recent decades, extractivism has become integral to the global economy. Approximately one hundred countries, primarily in the Global South, focus on exporting raw materials, including fossil fuels, minerals, metals, and agricultural products (UNCTAD, 2023a). This uneven reliance on raw material exports leads to numerous problematic consequences, such as overexploitation of natural resources, environmental disasters, reduced job opportunities in other economic sectors, land concentration, fluctuating export prices, increasing technological dependence, suppression of environmental and labor rights, and social conflicts.

During the decolonization period in 1962, many Global South countries supported the doctrine of “permanent sovereignty,” which served as a political foundation for newly independent states to claim ownership of natural resource deposits within their territories. This political movement culminated in the drive towards a New Economic International Order (NIEO) (Laszlo et al., 1978; Veit & Fuchs, 2024). Raw material exports were already the subject of intense debate when the proposals for the NIEO were formulated. Even then, countries in the Global South had a substantial share of global commodity production but faced growing price challenges. They had to export increasing quantities of raw materials to continue financing technology imports, economic diversification, and prosperity.[4] An integral part of the NIEO was the proposal to modify the price system of the international economy so that the producing countries could generate higher revenues, which they could use for diversification and welfare. However, the NIEO failed in this topic. Resource-exporting countries were thwarted by the blockade of the industrialized countries, especially West Germany. But they also did not consequently enough integrate the topic of rent in their political claims. Eventually, the oil crises showed that the Global North could shield itself against economic claims from Global South economies. In the end, many economies in the Global South have remained extractive.

Since then, a heated debate has emerged regarding the root causes of this specialization pattern. On one side, Marxist and dependency approaches link raw material exports to the necessities of capitalist core countries and their imperialist, exploitative relationships with the Global South. On the other, (neo)classical and modernization theory-inspired approaches attribute the persistence of raw material exports to domestic structural factors.

The neoclassical perspective, exemplified by the Heckscher-Ohlin model, explains specialization through factor endowments: labor-abundant countries specialize in labor-intensive products, while capital-rich countries focus on capital-intensive production. In this model, assumptions such as full employment and sectoral factor mobility suggest that market forces will eventually promote convergence. However, empirical findings show that global asymmetries persist, especially between the North and South (Rodrik, 2013; Thompson & Reuveny, 2010). Marxist approaches, in turn, interpret these asymmetries as expressions of capitalist power relations. They point to unequal exchange and imperialism and argue that capitalist core countries structurally exploit the South. (Amin, 2018; Emmanuel, 1972; Ricci, 2019). Current developments, such as the discussions surrounding the “unequal ecological exchange” and “ecological imperialism,” emphasize ecological dimensions (Hickel et al., 2022; Infante-Amate & Krausmann, 2019). However, both approaches have limitations. Neoclassical models overlook persistent global inequalities and the lack of convergence, while Marxist approaches fail to account for shifts in specialization patterns within the global economy. Both perspectives also tend to oversimplify the dynamics of capitalism, reducing it to elite political agency (Warnecke-Berger, 2020).

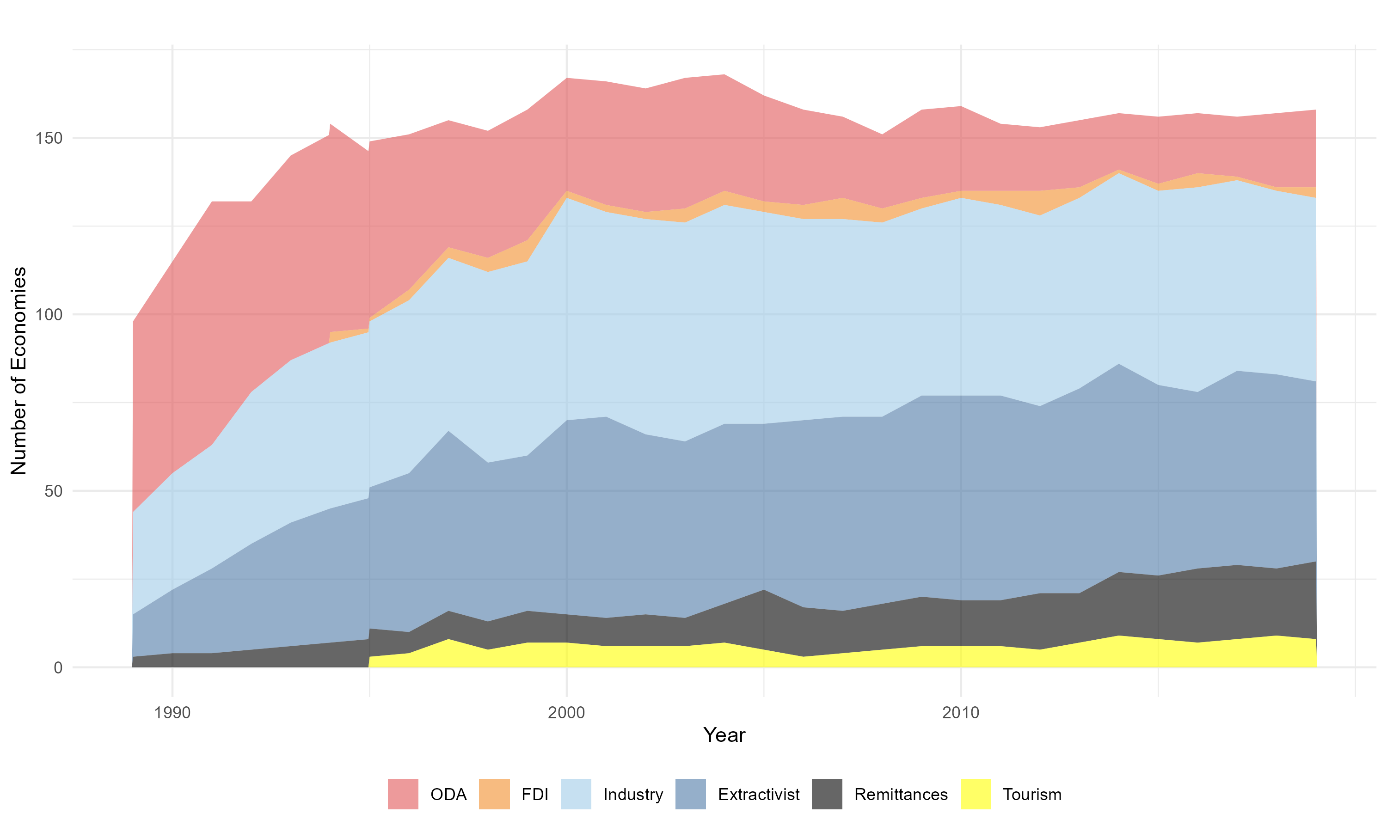

Against this theoretical debate, empirical trends need to be considered: While, on a macro level, extractivism is highly persistent, there are also three fundamental changes. First, the number of extractive economies that have shifted towards exporting labor-intensive manufactured goods is increasing. However, these countries often fall into the middle-income trap, struggling to increase either the technology content of their exports or industrial employment (Doner & Schneider, 2016). Second, the importance of countries that have moved from extractivism to specializing in labor migration and remittances is growing (Warnecke-Berger, 2022). Third, commodity-exporting countries are diversifying their exported commodities without overcoming extractivism as a development model. These trends indicate that the world economy is characterized by both continuity and transformation rather than absolute convergence or rigidity. Current political economy approaches must address these dynamics to explain the evolving global asymmetries and specialization patterns. Figure 1 underlines these developments. The number of economies having specialized in either extractivism or manufacturing exports (industry), has remained almost stable. However, the countries focusing on capturing remittances and tourism have increased.

Figure 1: Specialization Patterns[5]

Adding a heterodox approach to the discussion, we contend that the concept of unequal specialization can grasp both continuity and change of specialization patterns and extractivism within the global economy. We define unequal specialization as a process in which economies follow comparative cost advantages, specializing in product groups that yield high export revenues but create distortions within the economy (Warnecke-Berger, 2024). Unequal specialization occurs when economies specialize “incorrectly” in the international division of labor due to rents. In countries with structural unemployment and dependence on technology imports, specialization patterns deviate from mainstream economic assumptions. They cannot produce the range of products demanded by the population locally, but maintain a rent-led export sector. Despite unemployment and technology gaps, these economies still manage to generate significant export revenues, particularly in raw materials. However, they are not able to provide prosperity for the entire population.

Unequal specialization prevents economies from generating sufficient employment opportunities, stimulating technological learning, or processing exported products domestically. Extractivism, the one-sided unequal specialization in the extraction and export of raw materials, is a prime example of unequal specialization. Unequal specialization is a consequence of the occurrence and persistence of rents: ultimately, unequal specialization arises from the persistence of rents. These rents create the illusion of productivity in specific sectors, as they generate substantial excess revenues beyond the input of investment and labor.

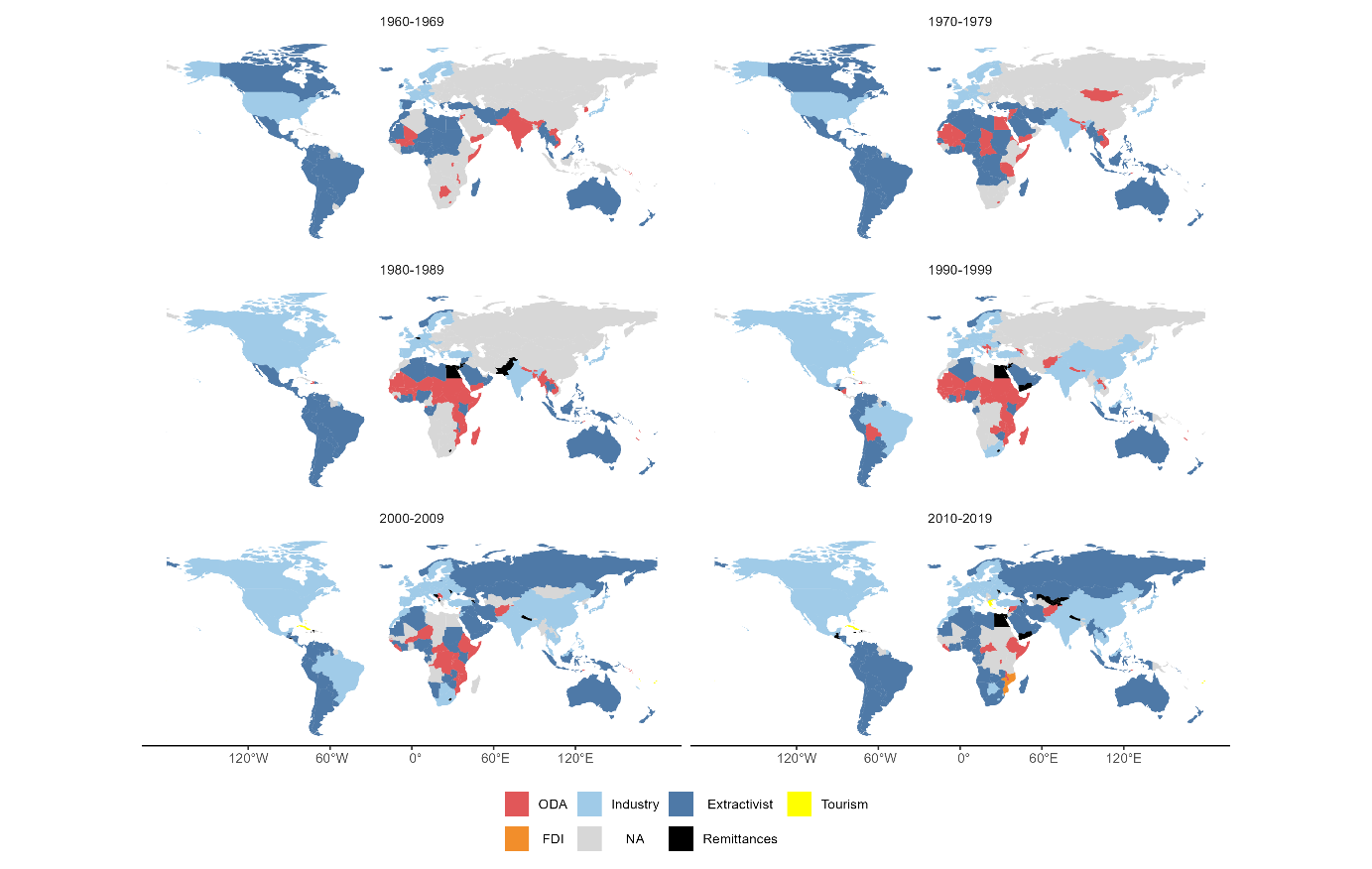

The following figure 2 exemplifies the specialization process on a country-level basis and presents 10-year average export data. The maps classify countries based on specialization in revenues from official development aid (ODA, red), manufacturing exports (industry, sky blue), natural resources (extractivism, steel blue), tourism (yellow), foreign direct investment (FDI, orange), or migrant remittances (black). Countries where data is unavailable are marked in grey.

Figure 2: Patterns in the World Economy, 1960-2020[6]

The figure shows that specialization follows a clear north-south axis. Countries in North America and Europe, and Asia for at least the last two decades have focused on industrial exports. Latin America and Africa, in contrast, are highly dependent on extractivism, with an increasing number of countries also emphasizing migration and ODA. The stability of this configuration highlights the role of rents in the global economy.

In this context, we have argued that rents play a vital role in explaining the distinct social, political, and economic features of extractivism on the one side and its persistence on the other. Both in the international economy as well as domestically, the omnipresence of rent makes overcoming extractivism difficult.

A Political Economy of Extractivism and the Future of the “Green” Economy

In summary, extractivism describes a development model based on the extraction and export of natural resources. Rents and their effect on economic structures, state institutions, politics, imaginaries, and actor constellations are critical for understanding the dynamics in extractivist countries. If rents become substantial for the material reproduction of a given society, political and economic logic reinforce each other, making alternatives to extractivism seem feeble. One key dynamic, thus, is the seductive force of rents on multiple levels.

We argue that rent theory provides a valuable lens through which extractivism and related phenomena can be analyzed. This perspective opens diverse research trajectories that engage with ongoing debates on contemporary capitalism. Perhaps most significantly, examining rents and the political economy of extractivism can facilitate the study of processes at the levels of the global economy, the state, and local formations. From this perspective, several compelling research topics emerge:

- Rents and the Global Economy: The world economy is characterized by fundamental asymmetries, and the neoclassical promises for convergence have not materialized so far. The dynamics of these asymmetries present an essential research issue within a broader perspective on the political economy of rent. Rent can be channeled into development or spent on repression and self-enrichment. In any case, when rents dominate surplus structures, political power outperforms market forces. This also opens space for intelligent policies for distribution and employment.

- Social Inequalities in Rent Societies: Social inequalities fundamentally characterize extractivist societies. Highly productive extractive sectors often discriminate against alternative economic activities, as the discussion on the Dutch Disease (Cordon, 1984) for example shows. The decoupling of economic sectors is usually dubbed structural heterogeneity, but informality and economic stagnation follow as well. Rents also present opportunities for governments to increase government spending on social reforms. A political economy perspective on rent illuminates who is benefiting and losing from these processes and, therefore, fundamentally incorporates distribution. This perspective also underlines the class dynamics that shape the use of rents and its impact on demand structures.

- Political Rule, State Institutions, and Power Relations: Extractivism is often equated with authoritarianism (for example, in the Gulf region). However, as the examples in Latin America or Norway show, extractivism is also compatible with democratic regimes. Nonetheless, the question arises whether and to what extent rents undermine democratic rule. As rent societies are prone to clientelism, patronage, and verticalized power structures, the political economy of rent can illuminate how politics are organized.

- Industrial Policies and Rent Management: Escaping Extractivism? Promoting structural change in extractivist societies is complicated. The ubiquity of rent and its political and economic dynamics tend to stabilize the status quo. Nonetheless, in the presence of rents, the question arises if and under what conditions rent can be used to promote alternative and possibly more sustainable economic activities. What are suitable industrial policies to contribute to structural change? How can exports be diversified and demand for domestic products increased? Which technologies and skills are needed to establish non-extractivist sectors?

Many of these questions can be studied within extractivist countries. Those studies provide insights into the mechanics of extractivism and the role of rents at both the national and local level. However, with extractivism being persistent and new economic shifts on the horizon, the relationship between extractivist and non-extractivist countries will change as well. One example is the global energy transition, which will fundamentally reshape the world economy. Scenarios that outline a path toward a lower-emission world—capable of effectively countering climate change—are based on several critical assumptions but usually share a high technicist perspective. (International Energy Agency [IEA], 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA], 2022). New, efficient technologies have the potential to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions by replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources. These technologies are not just adopted for their efficiency; their lower costs drive widespread adoption. However, we must recognize that the production of these technologies demands significant quantities of mineral resources, necessitating a substantial expansion in their extraction, allowing many Global South countries again to unequally specialize in extracting and exporting these new raw materials to the industrial centers of the world.

Under a development trajectory dominated by "green" technologies that fail to address domestic inequalities and global asymmetries, this shift is likely to generate additional rents within the international economy (Warnecke-Berger, 2025a). Producers of critical raw materials for the energy transition face varying production costs, and those with lower costs stand to generate significant rents if global demand remains high. In the case of materials like lithium—essential for renewable energy technologies—price disparities can be extreme, sometimes reaching ratios of one to twelve. This means that countries like Argentina and Chile may experience substantial rent gains. However, these rents could reinforce the tendency toward unequal specialization in extractive industries, limiting prospects for overcoming global asymmetries and inequalities. This, ultimately, represents the darker side of sustainability.

References

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Profile Books.

Amin, S. (2018). Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx's Law of Value. Monthly Review Press.

Bairoch, P. (1993). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press.

Barbier, E. (2019). Natural Resources and Economic Development. Cambridge University Press.

Bresser-Pereira, L. C. (2020). Neutralizing the Dutch Disease. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 43(2), 298–316.

Bruna, N. (2023). The Rise of Green Extractivism: Extractivism, Rural Livelihoods and Accumulation in a Climate-Smart World. Routledge.

Burchardt, H.‑J. & Dietz, K. (2014). (Neo-)Extractivism – A New Challenge for Development Theory from Latin America. Third World Quarterly, 35(3), 468–486.

Cerioli, L. & Warnecke-Berger, H. (forthcoming). Extractivism and International Studies. Oxford Encyclopedia of International Studies.

Chagnon, C. W., Durante, F., Gills, B. K., Hagolani-Albov, S. E., Hokkanen, S., Kangasluoma, S. M. J., Konttinen, H., Kröger, M., LaFleur, W., Ollinaho, O. & Vuola, M. P. S. (2022). From Extractivism to Global Extractivism: The Evolution of an Organizing Concept. Journal of Peasant Studies, 49(4), 760–792.

Chakraborty, S. & Sarkar, P. (2020). From the Classical Economists to Empiricists: A Review of the Terms of Trade Controversy. Journal of Economic Surveys, 34(5), 1111–1133.

Corden, W. M. 1984. “Booming Sector and Dutch Disease Economics: Survey and Consolidation. Oxf Econ Pap 36 (3): 359–80.

Dietz, K. & Engels, B. (2017). Contested Extractivism, Society and the State: An Introduction. In B. Engels & K. Dietz (Hrsg.), Contested Extractivism, Society and the State: Struggles over Mining and Land (S. 1–19). Palgrave Macmillan.

Doner, R. F. & Schneider, B. R. (2016). The Middle-Income Trap. World Politics, 68(4), 608–644.

Elsenhans, H. (1996). State, Class, and Development. Radiant Publishers.

Emmanuel, A. (1972). Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade. Monthly Review Press.

Evans, C. & Saunders, O. (2015). A World of Copper: Globalizing the Industrial Revolution, 1830–70. Journal of Global History, 10(01), 3–26.

Gudynas, E. (2020). Extractivisms: Politics, Economy and Ecology. Fernwood Publishing.

Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H. & Suwandi, I. (2022). Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain From the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467.

Ickler, J. & Ramos Padrón, R. (Hrsg.). (2025). Political Economy of Elites in Latin America. Routledge.

Infante-Amate, J. & Krausmann, F. (2019). Trade, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Colonial Legacy: The Case of France and its Former Colonies (1962–2015). Ecological Economics, 156, 98–109.

International Energy Agency. (2023). World Energy Outlook 2023. IEA Publications.

International Renewable Energy Agency. (2022). World Energy Transitions Outlook 2022: 1.5° Pathway. International Renewable Energy Agency.

Laszlo, E., Baker, R., JR., Eisenberg, E. & Raman, V. (1978). The Objectives of the New International Economic Order. Pergamon Press.

O'Brien, P. K. (1997). Intercontinental Trade and the Development of the Third World since the Industrial Revolution. Journal of World History, 8(1), 75–133.

Ricci, A. (2019). Unequal Exchange in the Age of Globalization. Review of Radical Political Economics, 51(2), 225–245.

Rodrik, D. (2013). Unconditional Convergence in Manufacturing. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 165–204.

Schmitz, C. (1986). The Rise of Big Business in the World Copper Industry 1870-1930. Economic History Review, 39(3), 392–410.

Shapiro, J. & McNeish, J.‑A. (Hrsg.). (2021). Our Extractive Age: Expressions of Violence and Resistance. Routledge.

Smith, B. & Waldner, D. (2021). Rethinking the Resource Curse. Cambridge University Press.

Storm, S. (2015). Structural Change. Development and Change, 46(4), 666–699.

Svampa, M. (2019). Neo-Extractivism in Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, W. R. & Reuveny, R. (2010). Limits to Globalization: North-South Divergence. Routledge.

United Nations Commission on Trade and Development, UNCTAD (2023b): The remarkable trade rebound of 2021 and 2022. United Nations.

United Nations Commission on Trade and Development. UNCTAD (2023a). Commodities and Development Report 2023: Inclusive Diversivication and Energy Transition. United Nations Publications.

United Nations. (2024). UN ComTrade Database. United Nations. https://comtradeplus.un.org/

Veit, A. & Fuchs, D. (Hrsg.). (2024). Eine gerechte Weltwirtschaftsordnung? Die »New International Economic Order« und die Zukunft der Süd-Nord-Beziehungen. transcript.

Veltmeyer, H. & Petras, J. F. (Hrsg.). (2014). The New Extractivism: A Post-Neoliberal Development Model or Imperialism of the Twenty-First Century? Zed Books.

Warnecke-Berger, H. & Ickler, J. (Hrsg.). (2023). The Political Economy of Extractivism: Global Perspectives on the Seduction of Rent. Routledge.

Warnecke-Berger, H. (2020). Capitalism, Rents and the Transformation of Violence. International Studies, 57(2), 111–131.

Warnecke-Berger, H. (2022). Rents, the Moral Economy of Remittances, and the Rise of a New Transnational Development Model. Revue de la régulation, 31(2).

Warnecke-Berger, H. (2024). Rohstoffe, Renten und ungleiche Spezialisierung: Über die Chancen einer neuen Weltwirtschaftsordnung. In A. Veit & D. Fuchs (Hrsg.), Eine gerechte Weltwirtschaftsordnung? Die »New International Economic Order« und die Zukunft der Süd-Nord-Beziehungen (S. 317–338). Transcript.

Warnecke-Berger, H. (2025a). Post-fossile Zukunft: Lateinamerika zwischen Rohstoffreichtum und ungleicher Spezialisierung. In H.-J. Burchardt, K. Dietz & H. Warnecke-Berger (Hrsg.), Grüne Energiewende in Lateinamerika (S. 81–102). Nomos.

Warnecke-Berger, H. (2025b). Surplus, Rent and Unequal Development: Raw Materials and Remittances as the Motor of Rent Societies in the Global South? In B. Sanghera (Hrsg.), Global Rentier Capitalism: Theory and Development (S. 210–224). Routledge.

Warnecke-Berger, H., Burchardt, H.‑J. & Dietz, K. (2023). The Failure of (Neo-)Extractivism in Latin America – Explanations and Future Challenges. Third World Quarterly, 44(8), 1825–1843.

World Bank. (2024). World Development Indicators Database. World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

[1] In this piece, we use natural resources, raw materials and commodities interchangeably.

[2] During his trip to Latin America he stated: „There is this expression – extractivism – which means that everything is just taken out of the earth. But that's not a good thing if that's all that happens. We want to help Chile move towards a sustainable mining sector.” „Es gibt diesen Ausdruck - Extraktivismus -, der besagt, dass alles nur aus der Erde herausgeholt wird. Aber das ist keine gute Sache, wenn das alles ist, was passiert. Wir wollen Chile auf dem Weg zu einem nachhaltigen Bergbausektor helfen.“ https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/energie/scholz-chile-rohstoffe-101.html

[3] Since social and political loyalty must be generated in order to appropriate rents, access to rents also depends on symbolic categories, social distinction, and specific modes of communication, which can generally be described as a process of social closure. Pensions can thus be translated into symbolic resources and group membership, which enhances the role of exclusive group affiliations in pension societies, such as religious communities, ethnic groups, political parties and other forms of horizontal inequality.

[4] This issue was the root observation of the terms-of-trade debate, which is still intensively discussed today, however, remaining controversial (Chakraborty & Sarkar, 2020).

[5] Source: own elaboration based on data from United Nations (2024); World Bank (2024).

[6] Source: own elaboration based on data from United Nations (2024); World Bank (2024).

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons-Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).